Executive Summary

- The real AI governance challenge: Who gets to decide what AI systems optimize for? Current debates miss that AI conflicts are between different groups of people, not humans vs. machines.

- Power flows from control of AI inputs: Those who control the means of prediction (data, computing power, expertise, and energy) determine AI objectives.

- Current governance approaches fail: Individual privacy rights and market mechanisms can’t address AI’s collective harms and benefits.

- Democratic control is the solution: Give stakeholders affected by AI decisions a voice in setting AI objectives.

Introduction

How should we regulate AI? This debate is often dominated by arguments between “AI boomers” and “AI doomers” (Hao, 2025). AI boomers claim that building “artificial general intelligence” (AGI) is the last problem that we need to solve. Once AGI has been built, it will then take care of the rest – continuously improving itself, while at the same time curing cancer, solving climate change, etc. AI doomers similarly believe that AGI, once it has reached the threshold of human intelligence, will continue to improve itself, but will ultimately – driven by self-preservation – eliminate humanity.

In my book (Kasy, 2025) (University of Chicago Press, October 2025), I argue that we need to step outside of this false dichotomy between AI boomers and doomers. Both boomers and doomers share problematic implicit assumptions: Both sides assume that the advent of AI is inevitable, intelligence is one-dimensional, there is a threshold of human intelligence, and beyond this threshold AI will exponentially self-improve. And both sides understand potential problems with AI only as conflicts between human and machine, which are described as problems of value alignment.

Against both boomers and doomers, I argue that the progress of AI is not fate but rather a product of human choices. The key conflicts are not between humans and machines but between different people. The answer to these conflicts is shared democratic control of AI and of the objectives that it pursues: Those impacted by algorithmic decisions need to have a say over these decisions.

In the following, I review and expand on this argument. I first discuss how all of AI involves optimization of some measurable objective. Social conflicts around AI are about the choice of these optimization objectives.

I then analyze how control of these objectives is based on control of the inputs into AI – the means of prediction – which include data and compute, but also expertise and energy. I will take a closer look at the production function of AI, which relates inputs of data and compute to the average performance in terms of the AI’s objective. I will draw on both statistical theory and empirical patterns observed by AI researchers in industry. These patterns, known as scaling laws in the deep learning literature, have guided the trajectory of the AI industry in recent years: They have motivated the massive scaling of data-centers for the training and deployment of AI models, which has lead to the concentration of control over AI in a small number of hands.

An analysis of the production function of AI provides the foundation for a discussion of the political economy of AI, and of conflicts over control of data, compute, and expertise. Externalities and market power are intrinsic features of this technology. I conclude with some proposals regarding how we might implement democratic control of the means of prediction, to give affected stakeholders a say over AI objectives, and to ensure broadly beneficial uses of AI.

Optimization errors and optimization objectives

What is “artificial intelligence” (AI)? Public perceptions have been subject to big swings – from thinking of AI as an obscure academic niche field, to AI as everything relating to data, and back to a narrower conception of AI as language modeling. For our discussion here, it will be most useful to think of AI as the construction of systems which maximize a measurable objective (reward). Such systems take data as an input, and produce chosen actions as an output. This is the definition provided by textbooks on AI, e.g. (Russell & Norvig, 2016).

There are many examples where AI, in this sense, is used in socially consequential and controversial settings. This includes the algorithmic management of gig-workers, and the automatic screening of job candidates to filter out applicants at risk of unionization. This includes ad targeting, and the filtering and selection of social media feeds to maximize engagement by promoting emotionalizing (political) content. This includes predictive policing and incarceration, and the jailing of defendants for crimes not yet committed. And this includes the automated choice of bombing targets and times, for instance by the systems “Lavender” and “Where is Daddy” in Gaza (Abraham, 2024). These systems were used to select individuals as targets and predict when fathers would be at home with their children, to bomb them together.

Based on the definition of AI as systems that optimize a measurable reward, much of the current debate around possible problems, ethical issues, and risks of AI focuses on optimization failures and mis-measured objectives. Social media algorithms might for example be criticized for maximizing short term click rates by providing click-bait, rather than maximizing long-term engagement. Algorithms assigning risk-scores to defendants in court might be criticized for failing to maximize incarceration rates of future perpetrators. Language models might be criticized for failing to provide answers evaluated as helpful by humans.

In (Kasy, 2025), I argue that this focus on failures to optimize the intended objectives misses the key issue: Applications of AI are typically not controversial because AI failed to achieve its objective. They are instead controversial because the chosen objective itself is controversial. Put differently, there is not just one objective that AI might or might not successfully maximize. Instead, different people have different objectives, and automated decisions generate winners and losers. Who gets to choose the objectives of AI is thus the crucial question.

In practice, the objectives are chosen by those who control the necessary inputs of AI. Almost all modern AI is built on machine learning, that is, on the automated statistical analysis of large amounts of training data. The most common form of machine learning is supervised learning, or prediction. In supervised learning, outcomes or labels are predicted given features: Unionization might be predicted given job applicant portfolios; ad-clicks might be predicted given user histories; future police encounters might be predicted given a defendants’ socioeconomic characteristics; whether a bombing target is at home might be predicted given mobile-phone based movement patterns.

Because so much of AI is based on prediction, the most important inputs of AI are the means of prediction – data, compute, expertise, and energy, in particular. Who controls these inputs controls AI.

Language models

Applications of AI such as those described above are both widespread and socially consequential, but not necessarily the most visible. Much of public attention in recent years has instead focused on large language models (LLMs), and on applications based on these, such as ChatGPT by OpenAI, or Claude by Anthropic.

Large language models are, in essence, statistical prediction models for the next word in a text, given the preceding words (Vaswani et al., 2017), (Jurafsky & Martin, 2023). They are trained on very large quantities of text; by now, essentially the entire internet, including transcribed Youtube videos. These LLMs also have a very large number of parameters, on the order of 100 billion at the time of writing (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Large_language_model). LLMs are trained iteratively, using a method called stochastic gradient descent (Bottou et al., 2018), until predictions stop improving for a hold out sample of data points that are not used directly in the training process.

The foundation models trained in this way are very powerful – they are essentially a compressed version of the entire internet (Chiang, 2023). But that is also where one of their key problems lies: The internet has many dark corners. These foundation models are quite prone to produce anything from genocidal propaganda to child sexual abuse materials. For this reason, these foundation models cannot be directly used for any application. Instead, they need to be post-trained, using human annotations. The process where language models are post-trained to predict responses that are flagged as “helpful” or “harmless” by human annotators is known as reinforcement learning from human feedback (Bai et al., 2022). An entire industry has sprung up hiring precarious, low wage workers in countries such as Venezuela or Kenya, who spend their days reading LLM generated descriptions of violence and abuse, flagging them as problematic where appropriate (Hao, 2025), and bearing the psychological costs that this work entails. Another variant of the post-training approach involves training on problems with well-defined solutions, from the domains of mathematics of coding. The LLMs are trained to predict the solutions of these problems, based on the problem description; the resulting capabilities have been branded as reasoning by the industry.

How does this description of LLMs fit into the general conception of AI as maximizing measurable rewards? The rewards that LLMs maximize during training are a weighted combination of (1) the ability to predict the next word on the internet, and (2) the ability to make predictions that get high ratings, according to the criteria specified for human feedback. It is in this second stage that owner values and objectives become most explicitly incorporated. At the time of writing, for instance, we could witness the transformation of Grok, the LLM controlled by Elon Musk, into a chatbot that regularly produces far-right and antisemitic posts.

Scaling laws and the production function of AI

AI models based on supervised learning need training data, and they need compute. Availability of both of these inputs is a binding constraint in practice. To understand the

relative importance of these different inputs, it is important to analyze the production function of AI. This production function of AI is a well-defined object: Because any AI system has an explicitly specified objective (reward), we can evaluate its output in terms of the average reward that it achieves. We can furthermore ask how performance in terms of this reward relates to the available inputs of data and compute.

I will first sketch the nature of this relationship theoretically. To describe the production function of AI, we need to review the concepts of overfitting, underfitting, and model complexity. I will then discuss the empirical counterpart of this relationship, which has received considerable attention in the industry. I lastly review how the estimated production function of AI has informed decisions in the AI industry over the last few years.

Theory of scaling laws

Statistical theory provides surprisingly specific characterizations of the production function of AI. In supervised learning, where the goal is to make predictions for new observations, the objective is to make small, or infrequent, prediction errors. For a given learning algorithm (prediction method), we can decompose the prediction error into two parts:

There is, first, the predictor variance. This is due to random fluctuations in the training data. An algorithm with a lot of variance is prone to overfitting – it erroneously extrapolates random fluctuations to new observations. As an algorithm gets more data, the variance goes down. That is why more data improves AI models.

There is, second, the predictor bias. This is typically due to the fact that the algorithm is too simple to faithfully reflect the true relationship between predictors and outcomes. A biased algorithm is prone to underfitting – it does not pick up on some patterns that are observable in the data. As an algorithm fits more complex models, the bias goes down – but the variance goes up. That is why more compute (which allows for more model complexity) improves AI models – but only if data is abundant.

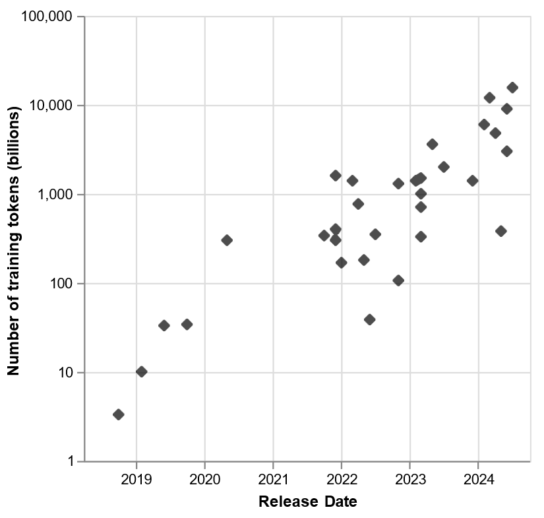

Any good prediction algorithm needs to carefully trade off underfitting and overfitting, by adjusting model complexity in some way or other. This is illustrated in the following figure (reproduced from (Kasy , 2025)). Models with low complexity tend to underfit, and lead to high prediction errors in both the training data and for out-of-sample observations (that were not used in training). As model complexity increases, prediction errors in the training data go down. But when complexity gets too large, the algorithm becomes prone to overfitting, and out-of-sample prediction performance deteriorates.

Figure 1: Prediction error and model complexity

In deep learning, this tradeoff is typically resolved by using early stopping, where training time determines effective model complexity: The algorithm continuously updates the neural network parameters (using a method such as stochastic gradient descent) to improve in-sample prediction errors. Along the way, prediction performance out-of-sample is evaluated using data that were set aside from the start. When out-of-sample performance stops improving, the training algorithm stops.

What does this description tell us about the production function of AI? The key inputs for training a model, such as a deep neural network, are (1) data, with a number of observations D, and (2) compute, as measured by the number of computational operations C. The necessary compute for training in turn is roughly equal to the number of model parameters (size of the neural network) N, times the number of training steps S, C = N ⋅ S. Deep learning practitioners acquire as much data D as they can, choose a model size N, and then train for a number of steps S determined by early stopping – or until they exceed their available budget of compute. They are thus interested in the production function L(N, D), which maps model size and data size into expected prediction loss. Model size N is chosen as a function of the compute budget C, N = N(C), to optimize performance.

Statistical theory, as sketched above, tells us a few things about the functions L(N, D) and N(C): (1) As data D increases, for fixed model complexity, loss goes down, because variance (overfitting) is reduced, but with decreasing marginal returns to sample size. (2) As compute increases, if training is compute-constrained, then loss goes down, because bias (underfitting) is reduced, but with decreasing marginal returns to additional compute. (3) If compute is not a binding constraint, then complexity C should increase with data size D to optimally trade off bias and variance.

More careful analysis allows us to quantify these patterns based on the difficulty of the underlying prediction problem. Theoretical characterization of scaling laws is the subject of an active are in theoretical machine learning research; see e.g. (Bach, 2023) and (Lin et al., 2025).

Empirical scaling laws for LLMs

Do these theoretical predictions hold up empirically? This question has been of central importance for the AI industry, especially since its pivot to a singular focus on large (language) models from around 2020: These models have required billions of dollars of investment in both compute and data. An analysis of production functions has been key for industry decisions regarding the allocation of resources, and in determining the expected returns (in terms of model capability) for large investments.

A series of papers, mostly authored by researchers at tech companies, has explored production functions for deep learning, by systematically varying the scale of model size N, compute C, and data size D. An early and very influential example is (Kaplan et al., 2020), by researchers at OpenAI. By fitting parametric models to expected loss, they obtained an empirical scaling law (production function) L(N, D), mapping inputs into predictive performance. In their experiments, a variety of architectural choices regarding how to structure the neural network used, such as depth versus width, appeared to be only of secondary importance.

These empirical patterns have since been revisited by a series of studies, such as (Hoffmann et al., 2022) at Google DeepMind, who proposed a production function (scaling law) of the form

L(N, D) = + + L0

where α = .34 and β = .28. This law tells us, in particular, how much predictive performance can be improved by scaling compute N, and also gives a lower bound L0 which can not be crossed regardless the scale of inputs, given the inherent entropy of language.

More recently, (Muennighoff et al., 2025) provide an empirical analysis in the case where data is the binding constraint, rather than compute – which is where language modeling finds itself at the moment.

Regardless of these various revisions, the basic point has held: Predictive performance scales with compute and data, but with decreasing marginal returns. Extrapolation suggested that very good performance could be achieved by scaling both compute and data, Reversely, the winner in a commercial race to dominate the AI industry needed to invest in acquiring both compute and data at a massive scale; dominance was not to be achieved by smart ideas around algorithm design alone.

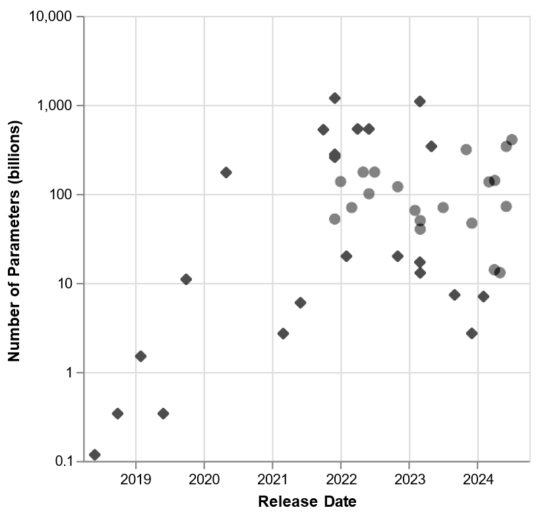

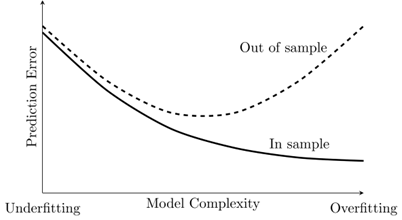

The scramble for scale

This recognition of empirical scaling laws has triggered a massive scramble for scaling large language models since around 2020. Both the number of training tokens D (tokens are sub-divisions of words; so this corresponds roughly to number of words), and the number of model parameters N, has increased exponentially. The following figure (reproduced again from (Kasy , 2025), based on data from Wikipedia, “Large Language Model,” accessed October 1, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Large_language_model) illustrates this scramble for dominance in the AI industry (note the logarithmic vertical scale on both plots!). This figure plots the number of training tokens D and the number of model parameters for the leading large language models, by model release date.

Figure 2a: Number of Training Tokens over time

Figure 2b: Number of Parameters over time

This scramble for scale has been extremely costly. Open AI, for instance, has raised a total of 57.9 Billion US$ at the time of writing (https://tracxn.com/d/companies/openai/ kElhSG7uVGeFk1i71Co9-nwFtmtyMVT7f-YHMn4TFBg, accessed February 10, 2026), much of which was spent on compute. The required data centers, for both training and deployment, have a large environmental footprint in terms of both energy and freshwater use (needed for cooling) (https://ig.ft.com/ai-data-centres/, accessed February 10, 2026). This scramble for scale has also made it impossible for any non-commercial entities to compete, crowding out much of the diverse academic AI ecosystem existing previously.

Future potential

Production functions can guide corporate allocation decisions. But they can also help us answer questions of broader societal relevance: (1) What future improvements can we expect from pursuing this technological path? (2) Who is going to reap the economic benefits of this technology? And (3) what levers do various actors have to reclaim democratic control of this technology in the public interest? We first discuss (1), before turning to (2) and (3) in the following section.

What is the likely trajectory of AI in the coming years? The most fundamental constraint, both for language models and for machine learning across a range of domains, is data availability. Once all the text on the internet, all existing books, and all auto-transcribed Youtube-videos have been fed into the training data, there is not much language data left that might be acquired.

This has prompted a number of reactions in the industry. First, more and more data of lower quality has been fed into these models, including data from the darkest corners of the internet. But that approach, too, seems to have largely run its course. Second, data “manually” annotated by humans, for specific tasks, has been collected, to create chat-bots such as ChatGPT. This has been crucial for turning generic language models into usable tools, but it is also time consuming and rather costly, and not easily scalable. Relatedly, curated problems with known true solution – in particular in math and in coding – have been used to guide language models towards problem-solving abilities. Third, there has been an attempt to scale compute not at training time (as described above, which has decreasing returns for fixed data size), but instead at inference time – whenever a user submits a prompt to the model. All of these have yielded some improvements, but they will not overcome the fundamental limits of scaling when data is, ultimately, limited.

Moving beyond language models, and turning our focus back to the many other socially consequential applications of AI, there is great variation in terms of the potential for an approach based on statistical learning. In domains where data is more limited than for language modeling, data can be expected to be the binding constraint, rather than compute. The potential for machine learning approaches is fundamentally governed by the amount of potentially available data, relative to the complexity of the underlying prediction problem. This holds regardless of the specific machine learning approach or model class used.

We can see this in a number of domains where the promise of machine learning has not been borne out, thus far. One example is genomics. After the initial excitement around the Human Genome Project in the early 2000s, many of the promised medical and scientific breakthroughs have not materialized (Ball, 2023). With hindsight, that might be not all that surprising: Given the number of genes in the human genome, and given that most biological processes involve complex interactions of multiple genes and environmental factors (contra the Mendelian model of one gene corresponding to one “trait”), the amount of observations needed for reliable predictive patterns greatly exceeds the number of living humans, whose genomes could possibly be sequenced. An intermediate example are self-driving cars. Despite partial successes based on complicated systems that combine many approaches, the promise of statistical learning leading to safe autonomous driving has not materialized thus far. Companies such as Tesla have however collected billions of hours of driving footage at this point, so maybe predictive performance will be sufficient for practical use at some point. Another example is macroeconomic forecasting: There is ultimately only one observation that we have of the US in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis; no amount of algorithmic tinkering will overcome the limitations this imposes on statistical extrapolation.

There are, of course, many other domains where the relationship of data-availability to complexity turns out to be more favorable. One extreme example is game-play in games such as go or chess, which has been solved using deep reinforcement learning (François-Lavet et al., 2018) by generating vast amounts of games based on self-play, which became possible once enough compute was available (Silver et al., 2017).

The scramble for data

Who gets to control the relevant inputs of AI, and thereby gets to control the objectives that are maximized? Who are possible agents of change, who have the ability and willingness to align the objectives of AI with socially desirable goals? What existing and legal instruments can be used to promote such alignment. What ideological obfuscations prevent us from doing so? (Kasy , 2025) discusses all these questions. Here I want to focus only on the question of control over data that describe individuals. Such individual data are the data that matter most for socially contested applications of AI.

Privacy and data externalities

Control over individual-level data is intimately connected to the question of privacy. The most well-known piece of privacy legislation is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union, which went into effect across Europe in 2018 and has since been adopted, with minor modifications, in a range of other countries. The GDPR gives wide-ranging control rights to individuals (data subjects) regarding data that concern them. We can interpret the GDPR as granting individual property rights over data.

Individuals can withhold their data, have them deleted, or share them at will, in exchange for services or other material benefits.

When such individual property rights over data are in place and effectively enforced, then data can only be collected if it is individually rational to share them. Companies that want to collect data, for example for the purpose of targeted advertising or individualized pricing, thus need to create mechanisms where individuals voluntarily share private information. Computer science has studied the creation of such mechanisms.

The literature on differential privacy (Dwork & Roth, 2014) in computer science provides a coherent formalization of how to make individuals indifferent about contributing their data, regardless of what downstream decisions might be made based on the output of the mechanism. This turns out to be equivalent to protecting the identity of individuals who contribute data to some dataset. Differential privacy is a property of mechanisms that release information about a dataset. Differential privacy requires that no one with access to the output of the mechanism can draw inferences about whether a specific individual is included in the dataset or not – regardless of what additional information or computational tools they possess. (Formally, these statements only have to hold with sufficiently high probability.)

There are many mechanisms that guarantee differential privacy. Any such mechanism needs to employ some degree of randomization. Importantly, as has been shown in machine learning theory, it is possible for supervised learning algorithms to learn predictive patterns without violating differential privacy. Consider the example of a linear regression, where an outcome Y is predicted using a linear function of features X with coefficients β, = X ⋅ β. Then it is possible to get a reliable estimate of β without revealing any information about whether any particular value of (Yi, Xi) was in the data (cf. (Dwork & Roth, 2014), chapter 11).

The upshot of these theoretical results is that machine learning is all about the patterns (β, in the regression example), not about the individual observations (Yi, Xi). This implies that differential privacy can be implemented without affecting any down-stream decisions based on machine-learning and AI. We can in particular have individual-property rights over data, and implement differentially privacy data-collection to make it individually rational to share, and yet leave all down-stream harms and benefits of AI unaffected!

To give an example, a health insurance company might learn how to predict certain diseases based on publicly available features Xi. Any individual might rationally be willing to share their health data, if these are protected by a differentially private mechanism. But after the insurance learns to predict the presence of the disease, all affected patients will be excluded from health insurance.

This is an example of what economists have called data externalities (Acemoglu et al., 2022). Because learning is all about externalities, individual data property rights are toothless for managing the harms and benefits of AI. This has led to calls for more collective forms of data governance (Viljoen, 2021); I will return to this point in the conclusion.

Artificial natural monopolies and network effects

There is a second reason why individual data property rights do not provide a solution. Even leaving aside the question of data externalities, we might be practically compelled to use certain platforms that collect our data, because being on the platform provides a positive benefit relative to any outside option or competing platform.

This is especially obvious for social networks: These networks are useful and enjoyable to the extent that they allow us to connect to other people or creators on the same platform. The platforms thus create network effects. Because it is almost impossible to collectively coordinate to switch to a different platform, these platforms look like natural monopolies; they are more useful the larger their user base is. This, in turn, implies that there is a surplus for any user who is on the platform, relative to the outside option. That surplus can be extracted by the platform by implementing surveillance and data-collection, even when surveillance is individually costly.

But are platforms really natural monopolies? Not quite: The network effects which sustain them are artificially and intentionally created – we might call them artificial natural monopolies. In fact, there is no technical reason whatsoever which prevents users on one platform from connecting with those on another platform. Consider, for comparison, how phone providers operate. When you want to call your friends, they don’t have to be using the same phone provider as you – phone networks are said to be interoperable. As a consequence, you can choose a phone plan without consideration of network effects, and there is actual competition between phone providers.

The network effects of digital platforms, from social media to gig work platforms, are thus artificially created. (Doctorow, 2023) coined the memorable term enshittification for the trajectory that such platforms undergo: At first, they provide quality service for free, to grow their user base. Then they actively prevent interoperability (which would technically be no problem to maintain) to create network effects. Once their user base is large enough, this by itself provides a surplus relative to alternative platforms. That surplus is then extracted, in particular in the form of data collection and surveillance.

Democratic control

To recap, artificial intelligence is automated decision-making to maximize some measurable objective. The most important question about AI is how this objective is chosen, and by whom. In practice, the objective is determined by those who control the means of prediction, in particular data and compute, as well as expertise and energy. In order to better align AI with socially desirable objectives, we need to create institutions that give those who are affected by AI decisions a say over the choice of the objective that is maximized.

Market-based mechanisms won’t allow us to achieve this goal. Machine learning and AI are fundamentally about the externalities of data collection and pattern recognition, so that individual property rights won’t allow us to regulate the harms and benefits of AI. Many applications of AI furthermore involve distributional conflict, which requires a social negotiation of the harms and benefits accruing to different people.

Consider social media: Algorithms that curate social media feeds typically maximize engagement. They often do so by promoting emotionalizing political content, which arguably undermines the democratic process and the possibility public deliberation of important questions. Consider individualized pricing and gig work platforms: Much corporate effort goes into data-collection for the purpose of estimating individual consumer demand or labor supply of gig workers. Machine learning then allows these companies to set individualized prices that maximize platform surplus, while extracting all consumer or worker surplus. Consider workplace automation: AI might be used in ways that either substitute or augment human workers, shifting marginal productivities up or down. How AI is deployed thus impacts whether it leads to shared prosperity or to a further concentration of wealth. The absence of market-based mechanisms to address social harms is even more glaring in the case of predictive incarceration or AI-based warfare and assassinations.

How, then, could we start building institutions for the democratic control of AI? We need effective legal frameworks that give stakeholders a voice – whether for social media-platforms, gig work, workplace automation, or predictive policing. Such voice, furthermore, cannot only be based on a check on a national ballot every four years.

Instead, it takes active deliberation and informed public debate across these domains. Such debate is possible. While the technical details of AI might be complicated, the fact that it maximizes well-specified measurable objectives is not.

Deliberation and decision-making across these domains could be based on various institutional arrangements. One attractive set of proposals involves sortition (Landemore, 2020), as familiar from jury duty: A randomly selected and representative set of stakeholders gets to meet regularly, to debate and acquire information, and to then make decisions. Another interesting option is liquid democracy: Rather than relying on a separate class of professional representatives, everyone is entitled to vote on important issues, or alternatively delegate their vote to any other individual, who in turn might delegate further. Digital tools can be used to facilitate this process.

This, then, is the main task for our future: To develop and implement institutions and mechanism for the democratic control the goals of AI by controlling the means of prediction. This is the only way for maintaining collective self-determination, and for aligning the objectives of AI with those of society at large, to avoid a dystopian future where we are ruled by AI systems acting in the interests of a small oligarchy.

References

Abraham, Y. (2024). “‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza”. https:// www .972mag .com /lavender – ai – israeli – army – gaza/ .

Acemoglu, D., Makhdoumi, A., Malekian, A., & Ozdaglar, A. (2022). “Too much data: Prices and inefficiencies in data markets”. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 14(4), 218–256.

Bach, F. (2023). “High-dimensional analysis of double descent for linear regression with random projections”. arXiv.

Bai, Y., Jones, A., Ndousse, K., Askell, A., Chen, A., DasSarma, N., Drain, D., Fort, S., Ganguli, D., Henighan, T., Joseph, N., Kadavath, S., Kernion, J., Conerly, T., El-Showk, S., Elhage, N., Hatfield-Dodds, Z., Hernandez, D., Hume, T., & Kaplan, J. (2022). “Training a helpful and harmless assistant with reinforcement learning from human feedback”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.05862.

Ball, P. (2023). How life works: A user’s guide to the new biology. University of Chicago Press.

Bottou, L., Curtis, F. E., & Nocedal, J. (2018). “Optimization methods for large-scale machine learning”. SIAM Review, 60(2), 223–311.

Chiang, T. (2023). “ChatGPT is a blurry JPEG of the web”. New Yorker.

Doctorow, C. (2023). The internet con: How to seize the means of computation. Verso Books.

Dwork, C., & Roth, A. (2014). “The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy”. Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science, 9(3–4), 211–407.

François-Lavet, V., Henderson, P., Islam, R., Bellemare, M. G., & Pineau, J. (2018). “An introduction to deep reinforcement learning. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 11(3–4), 219–354. https://doi.org/10.1561/2200000071.

Hao, K. (2025). Empire of AI. Penguin Press.

Hoffmann, J., Borgeaud, S., Mensch, A., Buchatskaya, E., Cai, T., Rutherford, E., Las Casas, D. de, Hendricks, L. A., Welbl, J., Clark, A., Hennigan, T., Noland, E., Millican, K., Driessche, G. van den, Damoc, B., Guy, A., Osindero, S., Simonyan, K., Elsen, E., & Sifre, L. (2022). “Training compute-optimal large language models”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.15556.

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2023). “Speech and language processing”. https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/.

Kaplan, J., McCandlish, S., Henighan, T., Brown, T. B., Chess, B., Child, R., Gray, S., Radford, A., Wu, J., & Amodei, D. (2020). “Scaling laws for neural language models”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361.

Kasy, M. (2025). The means of prediction: How AI really works (and who benefits). University Of Chicago Press.

Landemore, H. (2020). Open democracy: Reinventing popular rule for the twenty-first century. Princeton University Press.

Lin, L., Wu, J., Kakade, S. M., Bartlett, P. L., & Lee, J. D. (2025). “Scaling laws in linear regression: Compute, parameters, and data”. arXiv.

Muennighoff, N., Rush, A. M., Barak, B., Scao, T. L., Piktus, A., Tazi, N., Pyysalo, S., Wolf, T., & Raffel, C. (2025). “Scaling data-constrained language models”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.16264

Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. (2016). Artificial intelligence: A modern approach. Pearson Education Limited.

Silver, D., Hubert, T., Schrittwieser, J., Antonoglou, I., Lai, M., Guez, A., Lanctot, M., Sifre, L., Kumaran, D., Graepel, T., Lillicrap, T., Simonyan, K., & Hassabis, D. (2017). “Mastering chess and shogi by self-play with a general reinforcement learning algorithm”. https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.01815

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). “Attention is all you need”. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

Viljoen, S. (2021). “A relational theory of data governance”. Yale Law Journal, 131, 573.