Globalization and the rise of intangible capital have increased tax avoidance opportunities for large firms dramatically. 40% of multinational profits are shifted to tax havens each year globally and the United States loses about 15% of its corporate income tax revenue because of this shifting. I discuss the evidence on the redistributive effects of international tax competition. I then present a proposal to reform the corporate tax that would remove any incentive for firms to shift profits or move real activity to low-tax places. Contrary to a widespread view, it is possible to tax multinational companies (potentially at high rates) in a globalized world, even in the absence of international policy coordination.

Introduction

There is a widespread view that taxing the winners from globalization—multinational companies, wealthy households, highly skilled individuals—is hard if not impossible in a globalized world. Companies can move abroad or shift profits to tax havens; the wealthy can move too or hide assets offshore.

The view that taxing multinational corporations is fraught with difficulties finds support in the undeniable reality of tax competition. Between 1985 and 2018, the global average statutory corporate tax rate has fallen by more than half, from 49% to 24%. In 2018, most spectacularly, the United States cut its rate from 35% to 21%. This cut is likely to exacerbate the race to the bottom for corporate tax rates throughout the world in the years to come. In September 2018, Theresa May pledged to cut the U.K. corporate tax rate to the lowest rate among G20 countries post-Brexit. A number of other countries have announced their attention to further cut their rates (France, for instance, has planned to cut its rate from 33% today to 25% in 2022). Moreover, a large and growing fraction of profits are shifted to low-tax places. The prospects of taxing multinational companies at positive rates seem grim. Globally, some of the decline in corporate tax rates and loss of revenue caused by profit shifting has been compensated by base-broadening. But overall, the effective tax rates on corporate profits have declined a lot, almost in line with the decline in statutory tax rates (see Zucman, 2014). Moreover, in the United States the share of taxable corporate profits in GDP has fallen over time (due to the rise of the non-corporate business sectors and of tax-exempt corporations, known as S-corporations), reinforcing the decline in total corporate income tax revenue.

This essay argues that contrary to the widespread and intuitive view that corporate taxes are bound to fall, it is perfectly possible to combine globalization and the taxation of multinational corporations—including at high rates. Not only is this possible, but it is also necessary to make globalization sustainable economically and politically. It seems indeed unlikely that globalization will continue to proceed if its main winners pay less in less in taxes, while those who don’t benefit from it or are hurt by it—such as retirees, working-class individuals, and small businesses—have to pay more to make up for the lost tax revenue. For those who want to defend openness, it is critical to explain how globalization can concretely be combined with progressive taxation.

To contribute to this debate, I first discuss the evidence on the extent of corporate tax avoidance and the redistributive effects of international tax competition today. 40% of multinational profits are shifted to tax havens each year globally and the United States loses about 15% of its corporate income tax revenue because of this shifting. I then present a proposal to reform the corporate tax that would remove any incentive for firms to shift profits or move real activity to low-tax places. This reform would apportion the global, consolidated profits of firms proportionally to where they make their sales. Take a company that makes $10 billion in profits globally and 20% of its worldwide sales in the United States. In the reform I describe, 20% of this company’s global profits (i.e., $2 billion) would be taxable in the United States. Such a sales-based apportionment would put an end to profit shifting as it exists today and dramatically alleviate the pressure towards lower corporate tax rates.

The redistributive effects of tax competition

How much do the various countries of the world win or lose in profits today because of tax competition? Tax competition between nations affects the location of profits in two ways. First, multinational companies have incentives to move tangible capital from high-tax countries to places where taxes are low. As emphasized in standard models of tax competition (see, e.g., Keen and Konrad, 2013), this relocation increases wages in low-tax places (to the extent the capital and labor are less than infinitely substitutable) and it can increase or decrease welfare in these countries. It also reduces wages and unambiguously decreases welfare in high-tax places. In contrast to international trade (which can make losers within countries, but in standard theory enhances aggregate income in each country), tax competition makes some countries lose—and can even make most countries lose.

In addition to moving tangible capital to places where taxes are low, multinational companies shift paper profits to tax havens. They can do so in three ways: (i) by manipulating intra-group import and export prices (with affiliates in high-tax countries importing goods and services at high prices from related firms in low-tax countries), (ii) by using intra-group borrowing (with affiliates in low-tax places lending money to related firms in high-tax countries), (iii) by “locating” intangibles (such as patents, logos, algorithms, etc.) in tax haven subsidiaries.

Imagine that all countries had the same effective corporate income tax rate. That is, imagine there was perfect international tax coordination on both corporate tax rates and the definition of the tax base (same interest deduction and depreciation rules, for instance). In such a world, by how much would the profits booked by multinational companies in the United States rise compared to today’s world? And by how much would they fall in low-tax places such as Ireland and Bermuda? There are two ways profits would adjust: some of the tangible capital located in low-tax places today would move back to high-tax places and profit shifting would disappear. To quantify the magnitude of these changes—that is, who wins and loses from tax competition—it is helpful to start by studying where multinationals book their profits today.

Profit shifting by U.S. multinationals

A vast literature studies profit shifting by U.S. multinationals, for one simple reason: the U.S. data are particularly good. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis has a sophisticated statistical system to monitor its multinationals. A large sample of representative multinationals report detailed data annually to the Bureau since 1982; before that, benchmark surveys were conducted every five years. This dataset provides information about the foreign operations of U.S. multinationals abroad, including the profits booked in shell (or letter-box) companies in tax haven countries. Wright and Zucman (2018) use these data to study how much profits US multinationals have reported in each country and how much taxes they have paid abroad since 1966.[1]

Figure 1

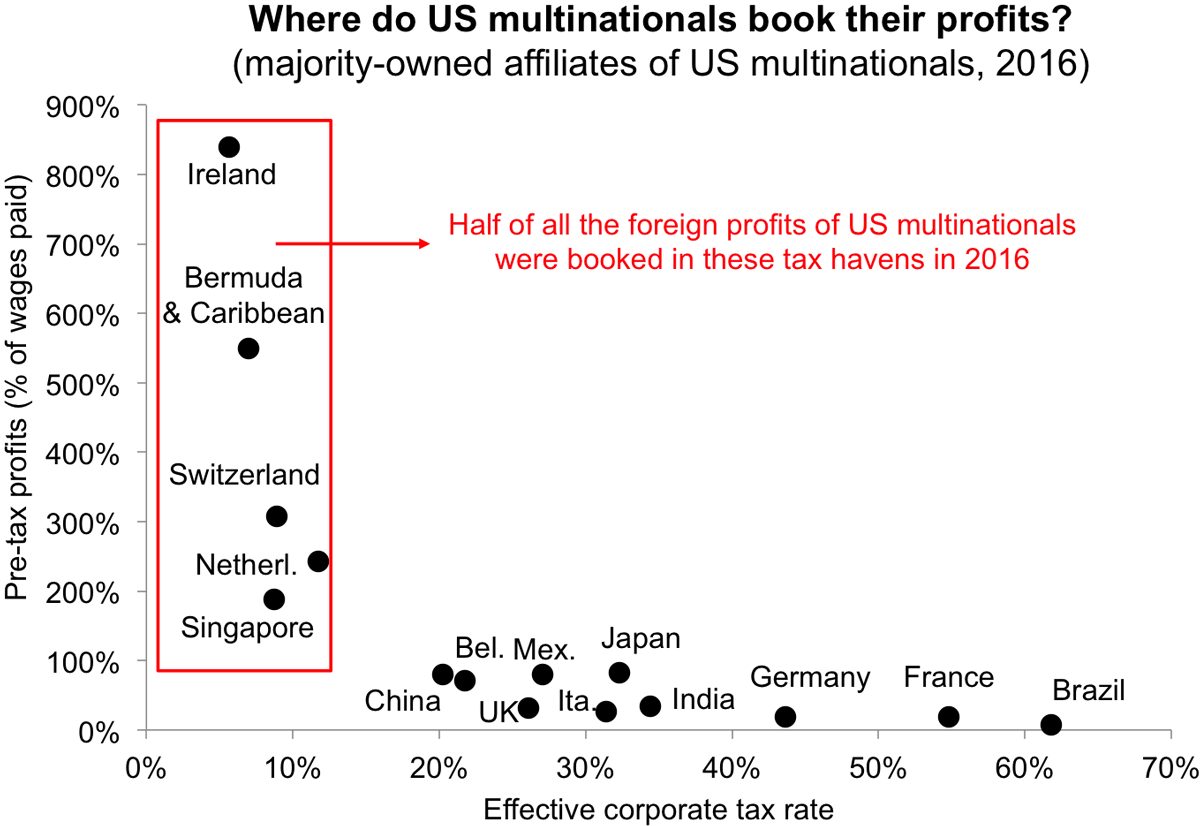

The latest available data are for the year 2016. In that year, US multinationals made $435 billion in profits abroad.[2] Almost half of these profits were booked in just 5 tax havens: Ireland, Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore, and Caribbean tax havens plus Bermuda. The amount of profits booked in Ireland alone ($76.5 billion) exceeds the profits booked in China, Japan, Mexico, Germany, and France together. Taking into account the profits shifted to Puerto Rico (not covered by the BEA data) and other tax havens, the data show that about 55% of the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals are booked in tax havens today. The profits booked in haven affiliates are enormous compared to the wages paid by these affiliates. In haven affiliates, the ratio of pre-tax profits to wages is around 350% (for any dollar of wage paid, U.S. multinationals say they make 3.5 dollars in pre-tax profits). In non-haven affiliates, this ratio is below 50%. In other words, the location of profits has become dramatically disconnected from where firms employ workers and from they produce goods and services more broadly.

It is not hard to understand why U.S. multinationals book such a high fraction of their profits in Ireland, Netherlands, and similar places. As shown by the Figure below, these countries impose taxes on the profits of U.S. multinationals at very low rates—in a range of 5%-10%. That is, taxes paid by U.S. affiliates to these countries amount to 5%-10% of the profits booked in these countries. There is a strong correlation between where U.S. multinationals book their profits and the effective tax rate they face. For small countries, imposing low rates of around 5% to foreign profits is revenue-maximizing in the current international tax system: it allows them to attract a huge tax base, which generates large revenue when tax rates only marginally higher than 0 are applied.

Global profit shifting

U.S. multinationals are not the only ones to shift profits to tax havens. By drawing on foreign affiliates statistics (similar to the BEA data) that were recently compiled in many economies, Tørsløv, Wier and Zucman (2018) estimate the extent of global profit shifting. They find that globally, 40% of multinational profits (profits made by corporations outside of the country where their parent company is incorporated) are booked in tax havens. This represents $600 billions of profits which are made in high-tax countries each year, but end up being booked and taxed at very low rates in tax havens. Note that 40% of multinational profits shifted offshore, although a large figure, is lower than for U.S. multinationals alone (55%). That is, although multinationals from all over the world use tax havens, U.S. multinationals appear to use them particularly extensively.

The tax revenue costs of tax competition are sizable for many countries. Tørsløv, Wier and Zucman (2018) estimate that the United States loses about 15% of its corporate tax revenue because of the relocation of profits to low-tax places. Although tax havens do collect revenue on the huge bases they attract, profit shifting significantly reduces corporate income tax payments globally: for each $1 paid in tax to a haven, close to 5$ are avoided in high-tax countries. More than redistributing tax revenues across countries, profit shifting thus redistributes income to the benefit of the shareholders of multinational companies.

To better understand the high profits booked by multinationals in tax havens, it is helpful to decompose them into real effects (more tangible capital used by foreign firms in tax havens) and profit shifting effects (above-normal returns to capital and receipts of interest). This distinction matters because these two processes have different distributional implications. Movements of tangible capital across borders affect wages, since tangible capital has a finite elasticity of substitution with labor. By contrast, movements of paper profits (i.e., profit shifting) don’t: for a given global profitability, whether income is booked in the United States or in Bermuda has no reason to affect workers’ productivity in either of these places. Tørsløv, Wier and Zucman (2018) find that the high profits of multinationals in tax havens are mostly explained by shifting effects. Tangible capital is internationally mobile—and there is evidence that this mobility has become slightly more correlated with tax rates over the last twenty years. But globally, machines don’t move massively to low-tax places; paper profits do. These offshore profits are not left dormant; they are either invested in global securities markets, or used for cross-border mergers and acquisition, or used as collateral for loans that finance investments in the United States or other countries.

Of course, this finding does not tell us what would happen in a world without profit shifting, nor does it allow us to predict what will happen in the future. Logically speaking, it is entirely possible that multinationals will start moving more tangible assets to low-tax places if policy-makers reduce profit shifting opportunities but tax rates remain different across countries. What the data suggest is that, so far, profit shifting has swamped tax-driven capital mobility. But to address the fundamental challenges that globalization raises for corporate taxation, it is important to formulate reform proposals that would not only reduce profit shifting, but also reduce the incentives of firms to move real activity to low-tax places. Otherwise the risk is we may exacerbate forms of tax competition that are even more harmful than the competition for paper profits that is observed today.

Taxing multinationals in a globalized world

The good news is that there is a way to tax multinationals in a way that addresses both tax competition for real activity and for paper profits. At the country level, the corporate income tax base can be made largely inelastic by apportioning the global, consolidated profits of firms proportionally to where they make their sales. Concretely, if Apple sells 20% of its products in the United States, the U.S. federal government would say that 20% of Apple’s global profits are taxable in the United States. This would put an end to profit shifting because firms cannot affect the location of their customers (they can’t move their customers to Bermuda; and if they try to pretend that they make a disproportionate fraction of their sales to low-tax places, this form of tax avoidance is easy to detect and anti-abuse rules can be applied). This would also put an end to competition for real activity, because in such a system there is no incentive for firms to move capital or labor to low-tax places; the location of production becomes irrelevant for tax purposes.

U.S. states have successfully taxed companies operating in multiple states this way for decades, so this is a tried and tested proposal. For instance, California, like all other States with a corporate tax, uses an apportionment formula to determine what fraction of corporate profits are taxable in California. Since 2013, apportionment is based on sales only: if a company makes 10% of its U.S. sales in California, then 10% of its U.S. profits are taxable in California (at a rate of 8.84% currently). Before 2013, the formula was more complicated, with apportionment based not only on the fraction of sales, but also the fraction of employment and tangible capital assets used in California by the corporation. Over time, the majority of U.S. States have gradually adopted apportionment formulas based mostly or only on sales. Other countries with sub-federal corporate taxes, such as Canada and Germany, use similar apportionment mechanisms. With globalization, countries are becoming more and more like local governments within a broader federation; and therefore using apportionment formulas like local governments have done for a long time is logical way forward.

Apportioning the global profits proportionally to where sales are made can be done unilaterally. International cooperation is always preferable, but because tax havens derive large benefits from tax competition, it is unlikely they will ever agree to meaningful changes to the international tax system (at least absent large economic sanctions). But any country is free to set its tax base as it sees fit; and not all countries need to use the same base (e.g., the same apportionment formula) for the corporate tax to work well. U.S. States have for a long time used different formulas (with some States such as Massachusetts apportioning profits based not only on the fraction of sales made in Massachusetts, but also the fraction of the capital stock in and wages paid in Massachusetts).

This reform of the corporate tax illustrates a simple yet powerful idea, namely that globalization and redistributive taxation are not incompatible. The corporate income is progressive, because although it is typically levied at a flat rate, equity ownership (and hence corporate profits) are very unequally distributed (see, e.g., Saez and Zucman, 2016 for evidence and equity—and more broadly wealth—concentration in the United States). The corporate tax reaches wealthy individuals regardless of whether profits are distributed to shareholders or retained within corporations. For example, although Facebook does not pay dividends, it pays corporate income tax (and would pay much more with sales apportionment of Facebook’s profits), and hence Mark Zuckerberg—Facebook’s main shareholder—indirectly pays taxes this way.

Of course, the corporate tax does not necessarily entirely fall on shareholders. In principle, part of it may be shifted to labor. The incidence of capital taxes depends on the elasticity of capital supply, the elasticity of labor supply, and the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor. If both the labor and capital supply elasticities are small relative to the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor, then capital taxes (such as the corporate tax) fall on capital and labor taxes fall on labor. In a closed economy, it is unlikely that the supply of capital is very elastic. In an open economy, tax competition makes the supply of capital more elastic—and hence can contribute to shifting the incidence of the corporate tax to labor. The reform described here would annihilate tax competition and dramatically reduce the capital supply elasticity. The corporate tax would fall, like in a closed economy, mostly on capital. Raising the corporate rate to 35% (as was the case until 2017) or to 50% (as was the case in the 1950s, 1960, and 1970s) would significantly increase the effective tax rate on wealthy individuals in the United States, and the overall progressivity of the U.S. tax system. In turn, this would contribute to curbing the rise of inequality which has reached extreme levels in the United States compared to other developed economies (Alvaredo et al., 2018), although an exact quantification of this effect warrants further research. Beyond the effect on inequality, such a move would make the tax system fairer and hence more legitimate, eventually contributing to making globalization more sustainable in the 21st century.

Endnotes

[1] The BEA data include two measure of profits: a financial accounting measure (“net income”) and economic measure (“profit-type return”). We use the economic measure, which in contrast to “net income” avoids double-counting of the profits of indirectly-held affiliates and excludes capital gains and losses. See the Appendix of Wright and Zucman (2018) for a detailed discussion.

[2] This figure excludes profits booked in Puerto Rico (of the order of $40 billion). Puerto Rico is a foreign country for US tax purposes (i.e., the federal corporate tax does not apply to profits booked in Puerto Rico) and is used extensively by US multinationals to avoid taxes.

References

Alvaredo, Facundo, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. 2018. The World Inequality Report 2018, Harvard University Press, http://wir2018.wid.world.

Saez, Emmanuel and Gabriel Zucman. 2016. “Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 519–578.

Tørsløv, L., Wier, L. and Zucman, G., 2018. “The Missing Profits of Nations”, NBER working paper No 24701.

Wright, Thomas, and Gabriel Zucman. 2018. ‘The Exorbitant Tax Privilege”, NBER working paper #24983.

Zucman, Gabriel. 2014. “Taxing Across Boarder: Tracking Personal Wealth and Corporate Profits”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4): 121-148.