In this brief, I discuss the current state of economic development policy, which tends to focus on interventions, usually funded with foreign aid, that are aimed at fixing deficiencies in developing countries. The general perception is that there are inherent problems with less-developed countries that can be fixed by with the help of the Western world. I discuss evidence that shows that the effects of such ‘help’ can be mixed. While foreign aid can improve things, it can also make things worse. In addition, at the same time that this ‘help’ is being offered, the developed West regularly undertakes actions that are harmful to developing countries. Examples include tariffs, antidumping duties, restrictions on international labor mobility, the use of international power and coercion, and tied-aid used for export promotion. Overall, it is unclear whether interactions with the West are, on the whole, helpful or detrimental to developing countries. We may have our largest and most positive effects on alleviating global poverty if we focus on restraining ourselves from actively harming less-developed countries rather than focusing our efforts on fixing them.

Introduction

Understanding how to eradicate global poverty and improve the economic wellbeing of the poor- est communities in the world is among the biggest challenges facing academics and policymakers today. To date, the fight against global poverty has tended to focus on the use of foreign aid and policy interventions as the primary tools that can be used to help developing countries and improve economic growth. In this brief, I discuss whether the current development strategies are the best we have employ and whether we are ignoring other obvious strategies that are beneficial. I find that while foreign aid can help, it can also make things worse. In addition, at the same time that this ‘help’ is being offered, the developed West regularly undertakes actions that are harmful to developing countries. It is possible that we might have our largest and most positive effects if we focus on restraining ourselves from actively harming less-developed countries rather than focusing our efforts on fixing them.

The Current Focus

One of the primary tools used to alleviate poverty is foreign aid, which is the transfer of money, commodities, or services from a foreign country or international organization for the benefit of the recipient country’s population. It takes the form of grants or concessional loans and is typically classified into economic aid, military aid, and humanitarian (emergency) aid. The most common form of aid is official development assistance (ODA), which is primarily comprised of bilateral grants. When using the term here, I am also including transfers across borders by foundations, religious organizations, and NGOs, but not remittances between friends and family.

On the ground, foreign aid is used to fund a range of projects that take a wide variety of forms. There is ample evidence that many of these projects have sizeable benefits. For example, we know that the deworming program, which was organized and implemented by the Dutch NGO International Christelijk Steunfonds Africa (ICS) in Busia Kenya, led to school attendance and higher adult wages (Miguel and Kremer, 2004, Baird, Hicks, Kremer and Miguel, 2016). We also know that in Kenya, large-scale unconditional cash transfers given by the U.S.-based NGO GiveDirectly (GD) increases household assets, monthly revenues, and psychological wellbeing (Haushofer and Shapiro, 2016, 2018).

While there are clearly benefits, there are also many who voice concerns that foreign aid may also have other unintended effects that are deleterious. Because such effects are unexpected and unforeseen, they tend not to be measured or evaluated. Thus, we have a very poor understanding of the magnitudes of such effects. However, there are many reasons to think that they are non- trivial.

One established fact about the aid industry is that foreign aid is generally shaped by the strategic or economic needs of the donor countries (e.g., Alesina and Dollar, 2000, Kuziemko and Werker, 2006). Historically, the majority of foreign aid has been “tied,” meaning that the concessional loans or grants that are given come with the requirement that they be used to purchase the products of the donor country. The United States continues to be the country with one of the highest proportions of aid that is tied. While the tying of aid is beneficial for the donor country since it is effectively a form of export promotion, it poses significant costs for recipient countries. It is estimated that the tying of aid raises the costs of goods and services by 15–30% on average and for food aid specifically this figure is over 40% (Clay, Geddes and Natali, 2009).

We also know that large proportions of aid go missing. Reinikka and Svensson (2004) study World-Bank-funded capitation grants in Uganda that were intended to pay for all education- related expenses other than teacher’s wages and buildings. The authors develop a way of measuring the amount of the funds that actually reached the school. They find that the median school in their sample received 0% of its funds (i.e., 100% was stolen). Across all schools, on average, 87% of the funds went missing. Using the same protocol, they also find similarly high rates of fund capture elsewhere: 49% in Ghana, 57% in Tanzania, and 76% in Zambia. This theft is not isolated to the African context. Years later, Olken (2007) also applied the protocol to road maintenance aid projects in Indonesia and found that approximately 30% of funds went missing. Having such resources ‘up for grabs’ potentially affects the incentives of the most talented and entrepreneurial in a country, increasing the likelihood that they end up engaging in zero- sum rent-seeking activities rather than productive activities that are more likely to be beneficial for the country as a whole (Bhagwati, 1982). Although convincing empirical estimates of the causal effects of foreign aid on corruption remain elusive due to measurement and identification challenges, given the findings of Reinikka and Svensson (2004) and Olken (2007), it is almost tautological that aid increases corruption. Given that aid increases the amount of funds available, a fraction of which are stolen through corrupt activities, then this must increase the incidence and amount of corruption. Of course, it is possible that even though aid increases corruption today, because it increases economic growth, it may reduce corruption in the future. However, the evidence for growth-promoting effects of foreign aid remains elusive (Werker, Ahmed and Cohen, 2009).

Many academic studies have found explicit evidence for adverse consequences of foreign aid. Haushofer, Reisinger and Shapiro (2015) estimate the effects of unconditional cash transfers (UCT) on the neighbors of recipients. They show that one’s happiness is reduced when one’s neighbor receives an UCT. Interestingly, this is true whether or not the individual also receives a cash transfer. Werker et al. (2009) exploit variation in oil prices which drives aid contributions of oil-rich OPEC countries in the Middle East to less-developed Muslim countries around the world. They find that foreign aid does not affect investment or GDP growth. However, it does lead to a significant increase in household and government consumption, which primarily takes the form of increased imports of non-capital products. Thus, foreign aid does not fuel growth-promoting investments (or growth itself) but instead crowds out domestic savings and increases consumption of foreign products.

One of the most important adverse consequences of foreign aid is its potential influence on conflict. There are many accounts of foreign aid fueling conflict, such as the Nigeria-Biafra civil conflict of the late 1960s (Barnett, 2011, pp. 133–147) or the post-Rwandan-Genocide violence in the Eastern-DRC, which is still persisting 25 years later (Terry, 2002, ch. 5; Lischer, 2005, ch. 4).

Numerous studies have formally tested for relationships between foreign aid and conflict, using a range of identification strategies to obtain credible causal estimates and many have found that foreign aid increases conflict. Nunn and Qian (2014) find this to be the case for U.S. food aid. Their analysis uses an IV strategy where U.S. wheat production shocks, combined with a country’s tendency to receive wheat aid from the U.S., are used to obtain exogenous variation in U.S. food aid supply. Crost, Felter and Johnson (2014) use an RD strategy that exploits an eligibility cut-off for a World-Bank-funded development program in the Philippines to estimate the effects of the program on conflict. They find that eligibility to participate in the program is associated with more conflict, which appears to be due to an increase in insurgent attacks against government forces in an attempt to disrupt the program. Dube and Naidu (2015) estimate the effects of military aid in Colombia using a differences-in-differences identification strategy. They find that U.S. military aid leads to an increase in conflict and violence arising due to an increase in attacks by paramilitaries.

Others have argued that foreign aid is often channeled towards strengthening the government’s military, particularly in autocratic regimes where stability requires oppression and the use of force (Kono and Montinola, 2009). While it is unsurprising that military aid might have such an effect, this has actually been found for economic aid. This occurs through the sale of humanitarian aid (e.g., food aid) for cash, or by freeing up more of the government budget for military purposes. A recent analysis by Trisko Darden (2020) provides evidence, both through case studies and empirical analysis, for such an effect. The author finds that in the year following an increase in U.S. foreign aid into a country, there is an increase in killings, repression, and torture by the state. This is consistent with an earlier finding from Ahmed (2016), which shows that increased U.S. foreign aid is associated with greater repression and human rights abuses in the recipient country.

While there is evidence that foreign aid can have adverse effect, it is not true that it always has such effects. For example, in contrast to the findings of Haushofer et al. (2015), Egger, Haushofer, Miguel, Niehaus and Walker (2019) find positive economic spillovers, not negative, from a different UCT that was implemented by the same organization, but in a different part of Kenya, giving a different amount, and using a different randomization procedure. Nunn and Qian (2014) show that among the countries in their sample without a recent history of past conflict, food aid does not increase conflict. In a follow-up study that studies a conditional cash transfer program also in the Philippines, Crost, Felter and Johnson (2016) find that this aid package actually decreased conflict. Trisko Darden (2020) finds that the effect of U.S. aid on state killings and repression of its citizens is weaker following the end of the Cold War.

The fact that the effects of foreign aid appear to be so variable raises the natural next question is how to implement aid projects in a manner that minimizes harm and maximizes overall benefit. A recent study by Moscona (2019) takes an important step in this direction by estimating the heterogeneous effects of the universe of World Bank lending projects from 1995–2014. He finds that the conflict-promoting effect of foreign aid is greater when projects are less successfully implemented, which is measured by project quality scores given by the World Bank Independent Evaluation Group. Put simply, better-run aid projects generate less conflict. According to the estimates, having the worst-implemented aid projects results in more conflict than having no aid project at all and having the best-implemented aid projects results in less conflict than having no aid project. These findings nicely sum up the message that has emerged from anecdotal examples and from the case-study literature (e.g., Anderson, 1999). Foreign aid, if implemented successfully, can help. However, if poorly implemented, foreign aid projects can actually make things worse.

Other Options: Refrain From Harming

Given the issues associated with foreign aid, the natural question of whether other policy options are feasible immediately comes to mind. I now turn to a discussion of possible alternatives.

A commonly used tool by countries has been trade and industrial policies. The underlying logic of the policies is motivated by the fact that there is a remarkably strong relationship between a country’s level of economic development and what it produces (Hausman, Hwang and Rodrik, 2007). Without exception, countries producing sophisticated high-end manufactures, like automobiles and electronics, are relatively wealthy. Given this relationship, many countries have taken steps to promote production in these industries. These include subsidies, low-interest loans, and tariff protection. Evidence is now accumulating that successful implementation of these policies can promote the level of production (and even the productivity) of these industries, helping to jump-start industrialization and economic development. We now have evidence for the longer-run success of such policies, and their ability to have macro-level growth effects, from 19th century France (Juhasz, 2018), late 19th and early 20th century Canada (Harris, Keay and Lewis, 2015), late 20th century South Korea (Lane, 2017), post-WWII Italy (Giorcelli, 2019), and post WWII Finland (Mitrunen, 2019).

The evidence that industrial policy can jumpstart economic development appears compelling. While the exact mechanisms remain to be fully understood, knowledge externalities, learning by doing, increasing returns, and endogenous factor accumulation appear to be important. An important open question is whether the gains identified in the studies above are due to economic improvements, which are not zero-sum in nature, and which are due to a shifting of rents from other countries.

If we look at the historical record, it is clear that today’s industrialized countries relied heavily on industrial policy with very high levels of tariffs and trade restrictions (Irwin, 2002, Clemens and Williamson, 2004). These tariffs were a particularly important, and easy-to-collect, source of government revenue in a setting where state capacity was still limited. Because of multilateral tariff reductions due to the GATT/WTO, tariffs have declined significantly around the world. Developing nations have been forced to reduce their tariff restrictions to levels that are well below those that currently-industrialized nations had at the same level of economic development. While this is clearly economically beneficial for the world’s wealthiest nations, it has been argued that they are effectively “kicking away the ladder” of economic development (Chang, 2002). Now that they have industrialized, they are not allowing developing countries to use the same policy tools that they used to specialize in sophisticated products, whose production is closely linked to economic prosperity. Today’s developing nations are also being prevented from using these policies to collect scarce government revenue in settings where other forms of taxation, such as income tax, is challenging or impossible (Cage and Gadenne, 2018).

Under current WTO rules, there are cases when countries can obtain exceptions and apply sizeable barriers against foreign producers. Antidumping duties are one example of these. In theory, they are supposed to only be applied in cases where a foreign producer is engaging in ‘dumping’; namely, pricing goods below cost in an effort to drive all competitors from the market, after which they will then engage in monopoly pricing. In reality, anti-dumping duties have very little to do with anti-competitiveness and everything to do with traditional trade protection aimed at protecting domestic producers.

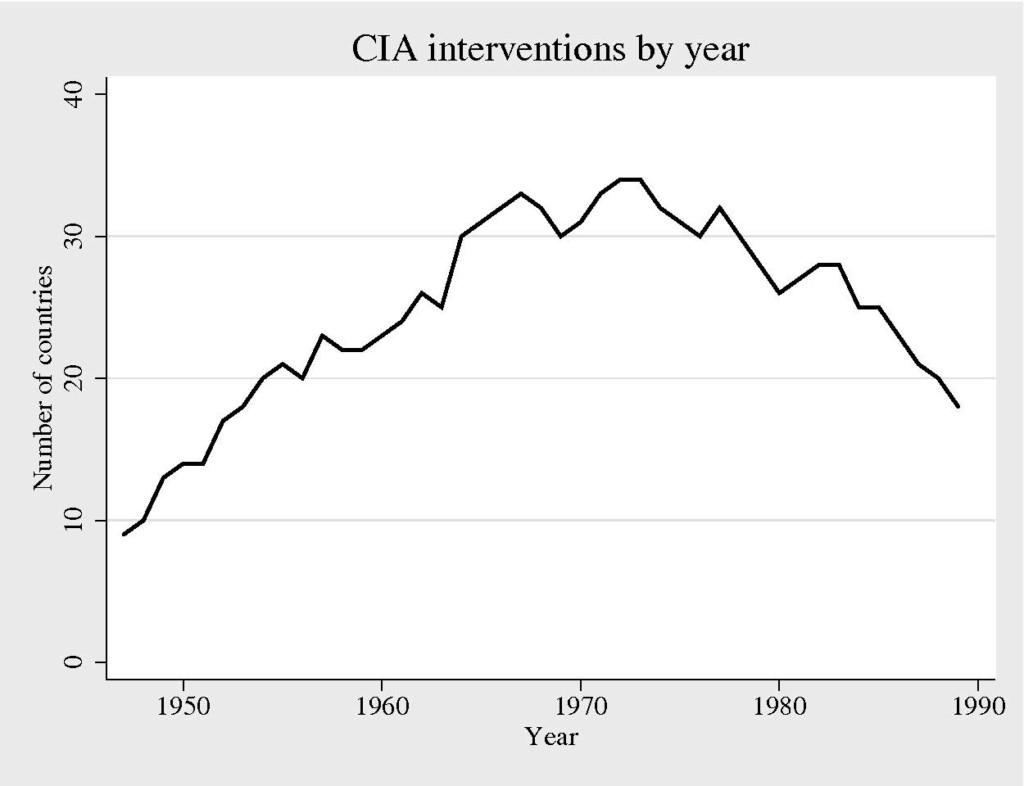

Antidumping duties have proven to be an effective and commonly-used tool. The duties applied are large, on average 10–20 times higher (and as much as 100 times higher) than MFN tariffs. On average, the duties cause the value of imports to fall by 30–50%. Strikingly, this decline in imports is found even if a case is only filed (i.e., initiated) but the duties themselves are never levied (Prusa, 2001). Thus, the threat of a duty only can have sizeable effects. Given this, it is not surprising that at the same time that (standard) tariffs have declined globally there has been a rise in anti-dumping duties. This increase, which is shown in Figure 1, has been sizable and rapid, especially during the 1980s and 1990s.

Figure 1: Total number of new anti-dumping initiations and measures each year from 1978–2013.

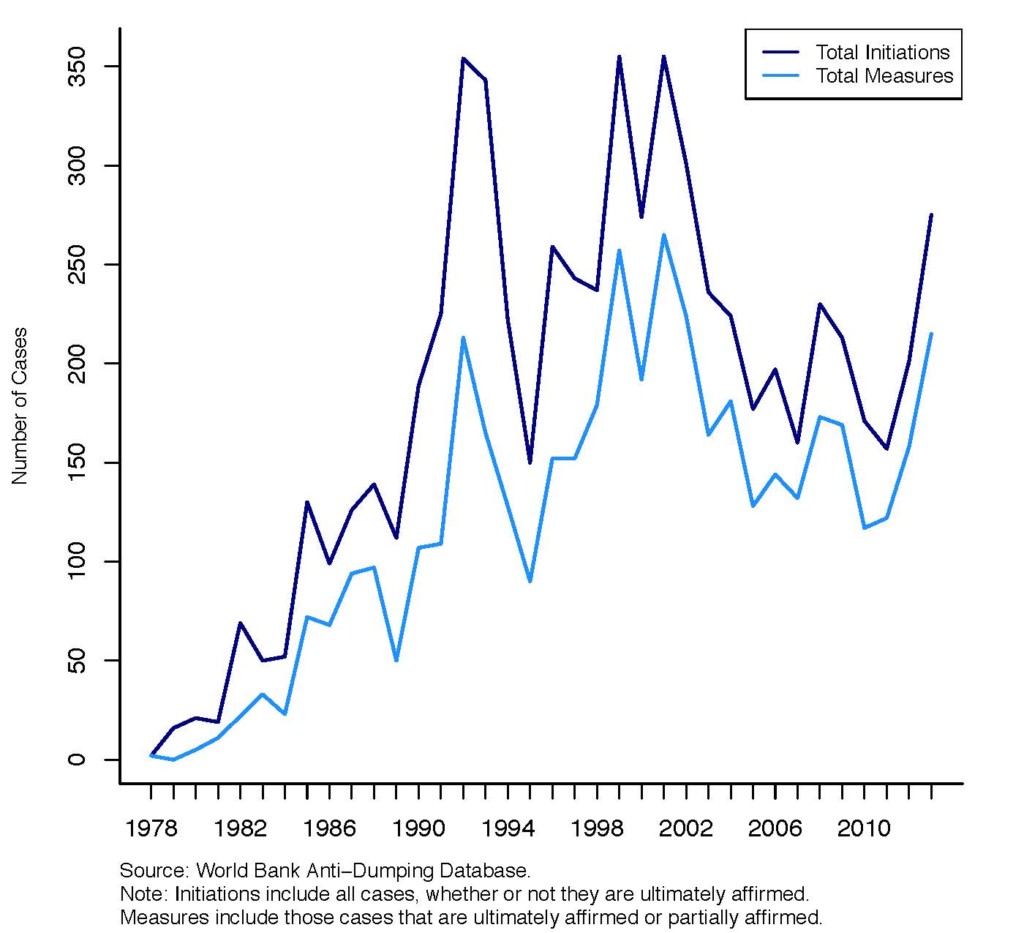

Since the initiation of antidumping duties requires significant legal capacity, they are typically initiated by wealthier countries and are often against less-developed countries. This is shown by Figure 2 which plot net initiations (i.e., initiations by a country minus initiations of other countries against the country from 1978–2013) and the country’s average income (measured in 1993). One observes a clear positive relationship. Countries initiating duties against others tend to be wealthier while countries that have duties placed against their products tend to be poorer.

Figure 2: Relationship between net anti-dumping initiations and average per capita GDP.

While the aggregate effects of these duties on developing countries are not fully understood, we do have some evidence from one duty (of the hundreds of duties that have been filed). This is for an anti-dumping duty that was placed against Vietnamese catfish farmers by Mississippi catfish farmers in 2003. The effects on Vietnamese households were studied by Brambilla, Porto and Tarozzi (2012). They find that for Vietnamese households that had specialized in catfish farming, average annual real per capita income decreased by 40%. This is an enormous effect and much larger than the size of any effect on incomes found for any form of foreign aid or any policy intervention.

If we were able to find an intervention that increased real per capita incomes by 40%, it would be the closest thing we have to a panacea for economic development. However, we effectively have a policy intervention that does this, which is to not impose these policies which significantly harm developing countries. Thus, by removing the current practice, which is aimed at shifting rents from the less developed world, we could tangibly reduce poverty. By comparison, consider The Millennium Villages Project, which was a high profile 10-year, multi-sector, rural development project, which began in 2005 in 14 village sites in ten countries (Mitchell, Gelman, Ross, Chen, Bari, Huynh, Harris, Sachs, Stuart, Feller, Makela, Zaslavsky, McClellan, Ohemeng-Dapaah, Namakula, Palm and Sachs, 2004). This project, with its multimillion-dollar price tag, induced an improvement in income that pales in comparison to the benefit that one would obtain by not initiating an antidumping petition against Catfish farmers in Vietnam.[1]

Antidumping duties are but one of many example of actions that developed countries take to the detriment of less-developed countries. There are many more examples. One that is closely related are tariffs and other trade restrictions more generally. There is ample evidence that, like anti-dumping duties, tariffs placed against developing-country products increase poverty, reduce growth, and retard industrialization (e.g., McCaig, 2011, McCaig and Pavcnik, 2018). Despite this, tariffs have, and continue to be, systematically higher against goods that developing countries produce. They are higher in less-skilled industries for which developing countries have a comparative advantage (Nunn and Trefler, 2013). Even within industries – i.e., at the product level – there is a bias against poor countries. Goods and varieties that are of lower quality, and tend to be produced by less-developed countries, have higher tariffs placed against them (Acosta and Cox, 2019).

Another example is the use of power and coercion in the international arena. Several papers have found that coercion has been used to benefit those with power (e.g., developed nations) at the expense of those without it (e.g., less-developed nations). Berger, Easterly, Nunn and Satyanath (2013) show that CIA interventions that led to the installment of ‘puppet’ leaders who were aligned with the United States, whether through propaganda, election support, organized coups, or assassinations, resulted in an increase in power that was used to create an export market for U.S. products. After ‘puppet’ leaders were installed, the sales of products from the U.S. to the intervened country increased dramatically, while the sales of the intervened country’s products to the United States did not change. The increased sales appear to have been due to the government purchasing products that the United States was having a hard time finding a market for.

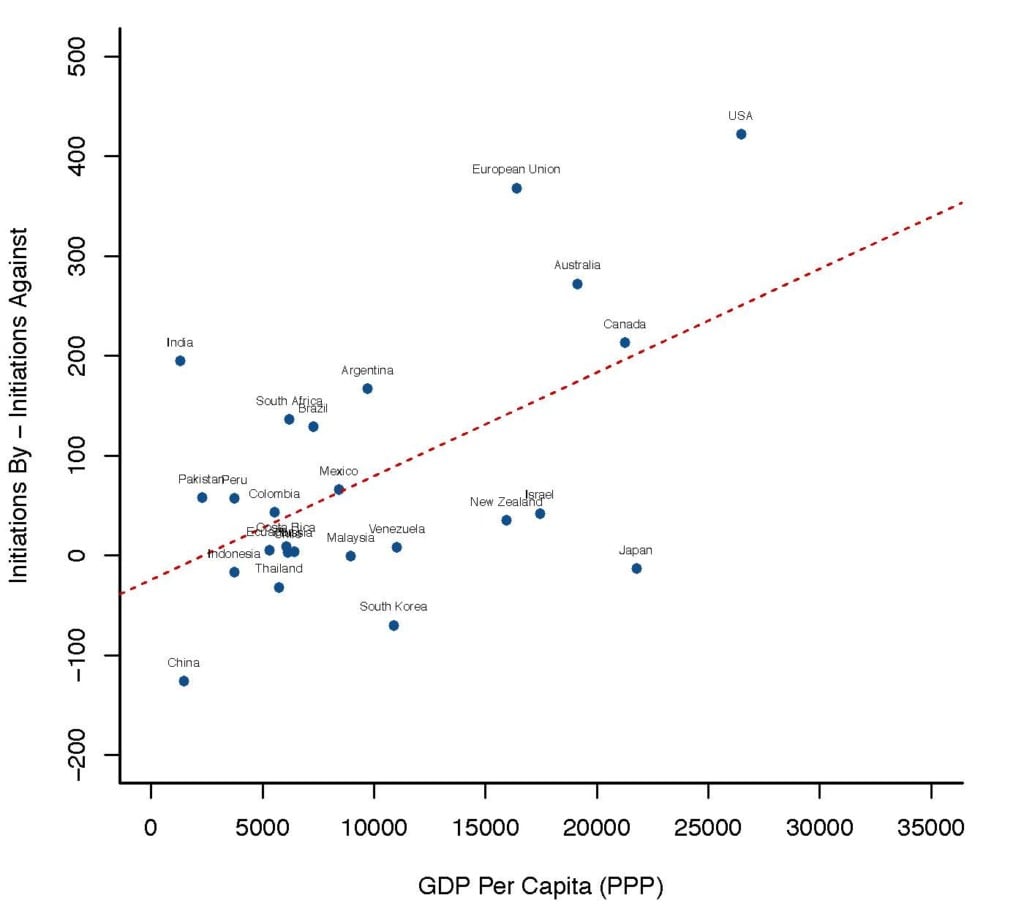

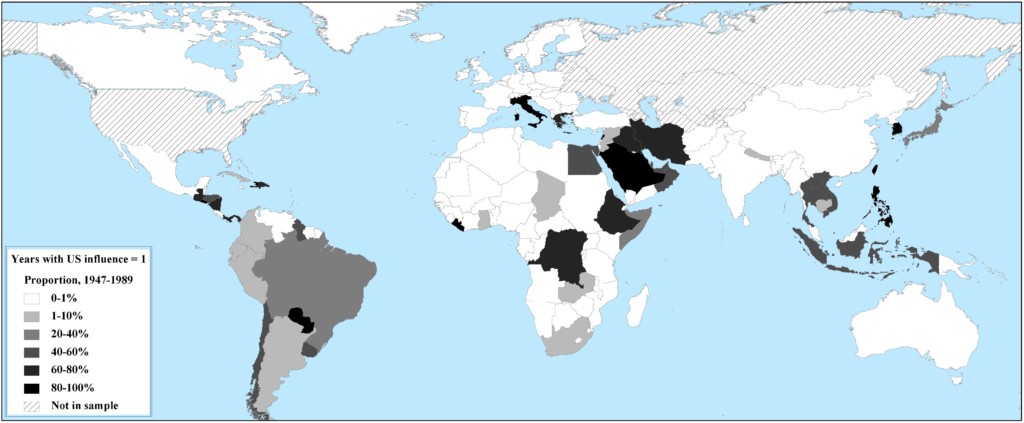

This form of foreign influence appears to be common and important. Figures 3 and 4 provide data from Berger et al. (2013) on the frequency of such events during the Cold War. Figure 3 shows the total number of ‘puppet’ leaders, who were installed and supported by the U.S. for each year of the Cold War, while Figure maps this for each country. Among the 166 countries in their sample, 51 were subject to at least one CIA intervention between 1947 and 1989 (and 25 countries were subject to at least one successful KGB intervention). In an average year between 1947 and 1989, 25 countries were experiencing a CIA intervention and among the countries that experienced an intervention between 1947 and 1989, the average country experienced 21 years of interventions.[2]

Figure 3: Total number of countries experiencing a successful CIA intervention in each year.

Source: Berger, Easterly, Nunn and Satyanath (2013).

Figure 4: Map showing the fraction of years between 1947 and 1989 with a CIA intervention.

Other forms of international coercion have also been identified in the literature. There is now ample evidence showing that coercion can also work through international organizations, such as the World Bank or IMF. As an example, Dreher and Jensen (2007) find that the number of conditions on IMF loans is lower if a country is politically aligned with the United States.

Another example is restrictions on labor mobility. There is now accumulating evidence showing that there are significant benefits to labor mobility. Not surprisingly, numerous studies have found that those who migrate benefit. A recent study by Clemens, Montenegro and Pritchett (2019) carefully accounts for selection into migration to obtain credible estimates of the causal effects of migration. They find that for unskilled male migrants with 9-12 years of education who move to the United States, migrating increases their annual real wage by 395% or $13,600 dollars. This illustrates an unsurprising but important fact: there is a remarkable increase in wellbeing for those who migrate. Also, if we presume that individuals are paid their marginal product, then this reflects a nearly 400% increase in the migrant’s productivity from moving to the United States.

For many, it is unsurprising that migrants themselves are better off after relocating. However, how could greater labor mobility be the basis of a serious development strategy? Won’t all developing countries empty and currently-wealthy countries will become overcrowded? This line of thinking, which is commonly used to dismiss attempts to increase the freedom of labor, ignores the fact that migration also makes developing countries – i.e., those left behind – better off. In fact, this is why this might be such a powerful development tool. Evidence shows that members of the extended family who are left behind are also made better off due to remittances (Yang, 2008, 2011), which themselves cause increased human capital accumulation, less child labor, and more entrepreneurship and self-employment (Yang, 2008). Quantitatively, the flow of remittances is large. Despite the limited migration that occurs currently, they already total more than aggregate aid flows (Yang, 2011). The potential benefits from migration due to remittances alone is large and with loosened migration restrictions remittances would easily swamp foreign aid flows.

It is not only the families that benefit when an individual migrates. Evidence is accumulating suggesting sending countries can also benefit from out-migration. As Sanchez (2019) has documented, in the late-19th Century, particularly successful emigrants from Spain, often financed public goods and other large-scale projects in their origin villages. Swedish emigration to the United States in the late-19th and early-20th Centuries led to higher unionization rates, more civic participation, and more inclusive domestic institutions within Sweden (Karadja and Prawitz, 2019) as well as greater innovation arising due to the resulting relative scarcity of labor (Andersson, Karadja and Prawitz, 2017). Emigration to the United States also led to more long-term inward and outward FDI for the sending countries. Thus, international migration facilitated the creation of international business links that continue to exist today (Burchardi, Chaney and Hassan, 2019). Kerr (2008) finds that immigration to the United States results in greater knowledge flows to the origin country, which results in greater productivity and output.

The last group that also benefits from migration is the receiving country. Sequeira, Nunn and Qian (2020) study immigration into the United States during its ‘Age of Mass Migration’. They find that immigrants generated sizeable economic benefits in the locations in which they settled. These benefits were felt almost immediately, persisted, and continue to be felt today. Such effects have been found in many different cases, including the 17th Century Huguenot immigration into Prussia (Hornung, 2014) to the large influx of Vietnamese refugees into the United States beginning in the 1970s (Parsons and Vezina, 2018) to immigration into France from 1995–2005 (Mitaritonna, Orefice and Peri, 2017). Clemens, Lewis and Postel (2018) study the effects of the elimination of the Mexican bracero worker agreement in 1964, a policy that resulted in the removal of nearly half a million seasonal Mexican farmworkers from the U.S. labor force. They find no evidence that domestic workers benefited from the exclusion, either in terms of higher wages or greater employment. Farm owners were forced to adjust to the scarcity of labor by shifting to labor-saving machines if such technology existed. If they could not do this, then they were forced to scale back production.

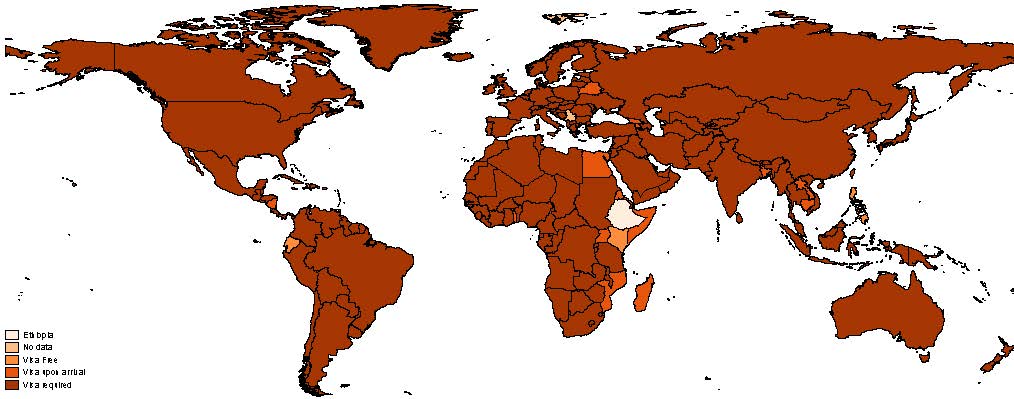

Admittedly, a complete loosening of immigration restrictions may not be realistic in the near future. However, the evidence also indicates that even small reductions in the costs of (temporary) mobility can have large effects. An example is restrictions on temporary travel visas, which are extremely stringent and onerous for travelers from many developing countries. Figure 5, which is taken from Umana-Dajud (2019), shows the visa restrictions facing an Ethiopians who wants to travel abroad. Each country is shaded according to restrictions an Ethiopian faces. Nearly every country in the world requires a visa to be obtained ahead of time. The handful of countries that allow a visa upon arrival do not actually have direct flights from Ethiopia and the transit countries all require a visa beforehand.

Figure 5: Visa restrictions faced by Ethiopians when traveling to each country.

We seem to have ended up in a strange equilibrium. With one hand, Western developed nations are taking actions that have obvious deleterious effects on developing countries. These decisions increase poverty and cause the persistence of underdevelopment. This occurs through trade policies, like tariffs or anti-dumping duties, and through practices in international relations and political economy. With the other hand, we are trying (or at least purport to be trying) to help developing countries through foreign aid, which we know often has unintended negative consequences and is typically given in a self-serving manner e.g., through tied-aid or aid given in-kind. It is likely that the very best thing that we as the West could do is to not take these actions that are causing harm. That is, we don’t need to “fix” anything. Instead, we could simply stop harming developing countries.

Conclusions

In this brief, I have reflected on the current state of economic development. As I have discussed, development policy tends to focus on interventions, typically funded with foreign aid, that are aimed at fixing deficiencies in developing countries. The general perception is that there are inherent problems with less-developed countries that can be fixed by with the help of the Western world. I have discussed evidence that shows that the effects of this ‘help’ can be mixed. While there are benefits, there can also be unintended adverse consequences.

At the same time that this ‘help’ is being offered, the developed West undertakes many actions that are harmful to developing countries in obvious ways. Examples include tariffs, antidumping duties, limits on international labor mobility, the use of international power and coercion, and tied-aid used for export promotion. These are but a few examples. Thus, it is unclear whether interactions with the West are, on the whole, helpful or detrimental to developing countries. We may have our largest and most positive effects on alleviating global poverty if we focus on restraining ourselves from actively harming less-developed countries rather than focusing our efforts on fixing them.

Endnotes

*For helpful comments and discussions, I thank Grieve Chelwa, Sahana Ghosh, Joseph Henrich, Jacob Moscona, Suresh Naidu, James Robinson, and Jessica Trisko Darden. I also thank Lydia Cox and Aditi Chitkara for excellent research assistance. Some of the arguments presented in this article can also be found in Nunn (2020).

[1] All this is not to say that the current system could not be better designed to improve global inequality. For one such proposal see the recent brief in this series by Dani Rodrik (2018).

[2] It is clear that such forms of international coercion are not a post-WWII phenomenon. There is a long history of economic coercion. Examples include the unequal treaties imposed by Western powers on China and Japan during the 19th and early 20th centuries (Findlay and O’Rourke, 2007).

References

Acosta, Miguel and Lydia Cox, “The Regressive Nature of the U.S. Tariff Code: Origins and Implications,” 2019. Working paper, Columbia University.

Ahmed, Faisal Z., “Does Foreign Aid Harm Political Rights? Evidence from U.S. Aid,” Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2016, 11 (2), 118–217.

Alesina, Alberto and David Dollar, “Who Gives Aid to Whom and Why?,” Journal of Economic Growth, 2000, 5 (1), 33–63.

Anderson, Mary B., Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace – Or War, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999.

Andersson, D., M. Karadja, and E. Prawitz, “Mass Migration, Cheap Labor, and Innovation,” 2017. Working Paper, Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.

Baird, Sarah, Joan Hamory Hicks, Michael Kremer, and Edward Miguel, “Worms at Work: Long-Run Impacts of a Child Health Investment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2016, 131 (4), 1637–1680.

Barnett, Michael, Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011.

Berger, Daniel, William Easterly, Nathan Nunn, and Shanker Satyanath, “Commercial Imperialism? Political Influence and Trade During the Cold War,” American Economic Review, 2013, 103 (2), 863–896.

Bhagwati, Jagdish N., “Directly Unproductive. Profit-Seeking (DUP) Activities,” Journal of Political Econ- omy, 1982, 90, 988–1002.

Brambilla, Irene, Guido Porto, and Alessandro Tarozzi, “Adjusting to Trade Policy: Evidence from U.S. Antidumping Duties on Vietnamese Catfish,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 2012, 94 (1), 304–319.

Burchardi, Konrad, Thomas Chaney, and Tarek Hassan, “Migrants, Ancestors, and Foreign Investments,” Review of Economic Studies, 2019, 86 (4), 1448?1486.

Cage, Julia and Lucie Gadenne, “Tax Revenues and the Fiscal Cost of Trade Liberalization, 1792–2006,” Explorations in Economic History, 2018, 70 (1), 1–24.

Campante, Filipe and David Yanagizawa-Drott, “Long-Range Growth: Economic Development in the Global Network of Air Links,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2018, 133 (3), 1395–1458.

Chang, Ha Joon, Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective, London: Anthem Press, 2002.

Clay, Edward J., Matthew Geddes, and Luisa Natali, “Aid Untying: Is it Working?,” An Evaluation of the Implementation of the Paris Declaration and of the 2001 DAC Recommendation of Untying ODA to the LDCs, Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS 2009.

Clemens, Michel A. and Jeffrey G. Williamson, “Why Did The Tariff-Growth Correlation Change After 1950?,” Journal of Economic Growth, 2004, 9 (1), 5–46.

, Claudio E. Montenegro, and Lant Pritchett, “The Place Premium: Bounding the Price Equivalent of Migration Barriers,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 2019, 101 (2), 201–213.

, Ethan G. Lewis, and Hannah M. Postel, “Immigration Restrictions as Active Labor Market Policy: Evidence from the Mexican Bracero Exclusion,” American Economic Review, 2018, 108 (6), 14689–1487.

Crost, Benjamin, Joseph Felter, and Patrick B. Johnson, “Aid Under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict,” American Economic Review, 2014, 104 (6), 1833–1856.

, , and , “Conditional Cash Transfers, Civil Conflict and Insurgent Influence: Experimental Evidence From the Philippines,” Journal of Development Economics, 2016, 118 (1), 171–182.

Dreher, Axel and Nathan M. Jensen, “Independent Actor or Agent? An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of U.S. Interests on International Monetary Fund Conditions,” Journal of Law and Economics, 2007, 50 (1), 105–124.

Dube, Oeindrila and Suresh Naidu, “Bases, Bullets, and Ballots: The Effect of U.S. Military Aid on Political Conflict in Colombia,” Journal of Politics, 2015, 77 (1), 249–267.

Egger, Dennis, Johannes Haushofer, Edward Miguel, Paul Niehaus, and Michael Walker, “General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya,” 2019. Working paper, University of California, Berkeley.

Findlay, Ronald and Kevin H. O’Rourke, Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Giorcelli, Michela, “The Long-Term Effects of Management and Technology Transfers,” American Economic Review, 2019, 109 (1), 1–33.

Harris, Richard, Ian Keay, and Frank Lewis, “Protecting Infant Industries: Canadian Manufacturing and the National Policy, 1870–1913,” Explorations in Economic History, 2015, 56 (1), 15–31.

Haushofer, Johannes and Jeremy Shapiro, “The Short-Term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers to the Poor: Experimental Evidence from Kenya,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 4 2016, 131 (1), 1973–2042.

and , “The Long-Term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya,” 2018. Working paper, Princeton University.

, James Reisinger, and Jeremy Shapiro, “Your Gain is My Pain: Negative Psychological Externalities of Cash Transfers,” 2015. Working paper, Princeton University.

Hausman, Ricardo, Jason Hwang, and Dani Rodrik, “What you Export Matters,” Journal of Economic Growth, 2007, 12 (1), 1–25.

Hornung, Erik, “Immigration and the Diffusion of Technology: The Huguenot Diaspora in Prussia,”American Economic Review, 2014, 104 (1), 84–122.

Irwin, Douglas A., “Interpreting the Tariff-Growth Correlation of the Late 19th Century,” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 2002, 92 (2), 165–169.

Juhasz, Reka, “Temporary Protection and Technology Adoption: Evidence from the Napoleon Blockade,” American Economic Review, 2018, 108 (11), 3339–3376.

Karadja, Mounir and Erik Prawitz, “Exit, Voice and Political Change: Evidence from Swedish Mass Migration to the United States,” Journal of Political Economy, 2019, p. forthcoming.

Kerr, William R., “Ethnic Scientific Communities and International Technology Diffusion,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 2008, 90 (3), 518–537.

Kono, Daniel Yuchi and Gabriella R. Montinola, “Does Foreign Aid Support Auocrats, Democrats, or Both?,” Journal of Politics, 2009, 71 (2), 704–718.

Kuziemko, Ilyana and Eric Werker, “How Much is a Seat on the Security Council Worth? Foreign Aid and Bribery at the United Nations,” Journal of Political Economy, 2006, 114 (5), 905–930.

Lane, Nathan, “Manufacturing Revolutions: Industrial Policy and Networks in South Korea,” 2017. Working paper, IIES Stockholm University.

Lischer, Sarah Kenyon, Dangerous Sanctuaries: Refugee Camps, Civil War, and the Dilemmas of Humanitarian Aid, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005.

McCaig, Brian, “Exporting Out of Poverty: Provincial Poverty in Vietnam and U.S. Market Access,” Journal of International Economics, 2011, 85 (1), 102–113.

and Nina Pavcnik, “Export Markets and Labor Allocation in a Low-Income Country,” American Economic Review, 2018, 108 (7), 1899–1941.

Miguel, Edward and Michael Kremer, “Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities,” Econometrica, 2004, 72 (1), 159–217.

Mitaritonna, Cristina, Gianluca Orefice, and Giovanni Peri, “Immigrants and Firms’ Outcomes Evidence from France,” European Economic Review, 2017, 96, 62–82.

Mitchell, Shira, Andrew Gelman, Rebecca Ross, Joyce Chen, Sehrish Bari, Uyen Kim Huynh, Matthew W. Harris, Sonia Ehrlichs Sachs, Elizabeth A Stuart, Avi Feller, Susanna Makela, Alan M. Zaslavsky, Lucy McClellan, Seth Ohemeng-Dapaah, Patricia Namakula, Cheryl A Palm, and Jeffrey D. Sachs, “The Millennium Villages Project: A Retrospective Observational, Endline Evaluation,” The Lancet, 2004, 6 (e500–e513), 725–753.

Mitrunen, Matti, “War Reparations, Structural Change, and Intergenerational Mobility,” 2019. Working paper, IIES Stockholm University.

Moscona, Jacob, “The Management of Aid and Conflict in Africa,” 2019. Mimeo, M.I.T.

Nunn, Nathan, “Rethinking Economic Development,” Canadian Journal of Economics, 2020, forthcoming.

and Daniel Trefler, “The Structure of Tariffs and Long-Term Growth,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2013, 2 (4), 158–194.

and Nancy Qian, “U.S. Food Aid and Civil Conflict,” American Economic Review, 2014, 104 (6), 1630–1666.

Olken, Benjamin, “Monitoring Corruption: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Indonesia,” Journal of Political Economy, 2007, 115 (2), 200–249.

Parsons, Christopher and Pierre-Louis Vezina, “Migrant Networks and Trade: The Vietnamese Boat People as a Natural Experiment,” Economic Journal, 2018, 128 (612), F210–F234.

Prusa, Thomas J., “On the Spread and Impact of Antidumping,” Canadian Journal of Economics, 2001, 34 (3), 591–611.

Reinikka, Ritva and Jakob Svensson, “Local Capture: Evidence from a Central Government Transfer Program in Uganda,” Journal of Political Economy, 2004, 119 (2), 679–705.

Rodrik, Dani, “Towards a More Inclusive Globalization: An Anti-Social Dumping Scheme,” 2018. Economics for Inclusive Prosperity Research Brief, December 2018.

Sanchez, Martin Fernandez, “Mass Migration and Education over a Century: Evidence from the Galician Diaspora,” 2019. Mimeo, Paris School of Economics.

Sequeira, Sandra, Nathan Nunn, and Nancy Qian, “Immigrants and the Making of America,” Review of Economic Studies, 2020, p. forthcoming.

Terry, Fiona, Condemned to Repeat: The Paradox of Humanitarian Action, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Trisko Darden, Jessica, Aiding and Abetting: U.S. Foreign Assistance and State Violence, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020.

Umana-Dajud, Camilo, “Do Visas Hinder International Trade in Goods?,” Journal of Development Economics, 2019, p. forthcoming.

Werker, Eric, Faisal Z. Ahmed, and Charles Cohen, “How is Foreign Aid Spent? Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2009, 1 (2), 225–244.

Yang, Dean, “International Migration, Remittances and Household Investment: Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Exchange Rate Shocks,” Economic Journal, 2008, 118, 591–630.

, “Migrant Remittances,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2011, 25 (3), 129–152.