What kind of voting system should countries have? This policy brief discusses the two main electoral systems in modern political democracies. It makes an argument that majoritarian systems such as what exists in the United States fail to properly represent voters. It suggests replacing the U.S. majoritarian political system with a proportional representation system and shows how this could be done within the context of current U.S. law.

Both economists and political scientists have worked on the impact of electoral systems. Empirical methods from economics as well as economic analysis of the incentives created by different political systems have contributed to our understanding of the consequences of electoral systems on representation. Additionally, economists have estimated the impact of electoral system on fiscal expenditures, something we will discuss towards the end of the policy brief.

There are two main voting systems in modern democratic societies: majoritarian systems and proportional representation systems. Federal voting in the United States is majoritarian though some states such as Maryland have proportional representation at the state level. In a majoritarian system, also known as a winner-take-all system or a first-past-the-post system, the country is divided up into districts. Politicians then compete for individual district seats. The candidate who receives the highest vote share wins the election and represents the district.

The main alternative to a majoritarian system is a proportional representation system. In a proportional representation system, citizens vote for political parties instead of individual candidates.[1] Seats in a legislature are then allocated in proportion to votes shares. In an ideal proportional representation system, a party that receives 23% of the votes nationwide also gets approximately 23% of the seats in the legislature.

Redistricting

One important aspect of a majoritarian system is that representation occurs by geographical district. In each district of a pure majoritarian system, whichever candidate gets a plurality of the vote serves as representative for that district. However, people move in and out of districts and thus district sizes change. As a result, most majoritarian systems have a redistricting process. In the United States, redistricting happens every decade after the population is counted in the Census.

One large problem with redistricting is that how districts are drawn can have a large influence on representation. For example, imagine that a country has 50% right wing voters and 50% left wing voters. Suppose the left-wing party gets to draw the district boundaries and suppose that ten districts need to be created. The left-wing party could simply pack right wing votes into one district by being creative with how it draws maps. If the left-wing party did this, there would be one right-wing seat with 100% right-wing voters. In the remaining areas, 5/9 of voters would be left-wing. Thus, the left-wing party could end up with nine of the ten district seats despite only having 50% of the votes by drawing its maps creatively. This is called gerrymandering.

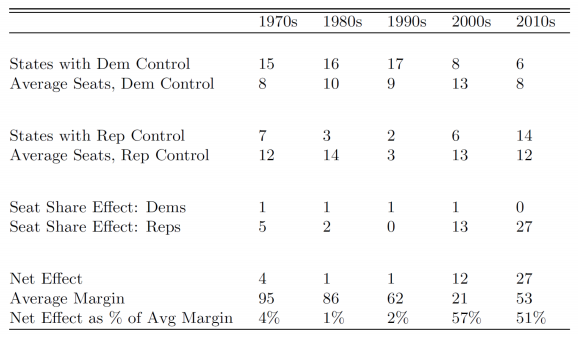

In a majoritarian political system, districts need to be drawn and redrawn and it is very easy to draw districts in order to benefit one political party over another. Unfortunately, in the United States, district maps are largely drawn by politicians. In most states, redistricting bills must be passed by state legislatures and signed by the Governor. All state legislature except for Nebraska have two chambers (an Assembly or House and a Senate). If a party has control over both chambers and the governorship, it can potentially redistrict without any input from the other political party. Coriale et al. (2020) show that in the past two decades, the average seat share gain in the House of Representatives from legal control by the Republican party over redistricting is an average of 8 percentage points over the subsequent three elections. Though we do not see a similar impact of Democratic control of redistricting on Democratic seat shares, we do for large Democratic states. Overall, these effects are sizable. They account for between 50% and 60% of the gap between the two parties in the House of Representatives in both the 2000s and the 2010s. Coriale et al. (2020)’s estimates of the impact of legal control are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Average Aggregate Partisan Effects of Partisan Redistricting by Decade

A move away from majoritarian electoral systems to proportional representation systems would get rid of political districts and, as such, would get rid of gerrymandering.

Geographic Concentration

There is a second problem with majoritarian systems. Even without parties manipulating district boundaries for political advantage, majoritarian systems can lead to systemic over-representation of some parties at the expense of others. For example, it is possible for the Democratic party to win just over 50% of the seats with only slightly more than 25% of the votes if the Republican party’s voters are concentrated in 100% Republican districts. This extreme failure of representation in a majoritarian system is interesting in theory but is it a problem in practice?

As pointed out by Rodden (2019), this has, in fact, become endemic in modern majoritarian systems. Political parties, over time, have become geographically polarized by population density with more urban areas further on the left and rural areas further on the right. There is now a clear spatial gradient with urban areas voting heavily for parties on the left, suburban areas voting moderately for the right, and rural areas voting more heavily for the right. This is not just true in the United States but also in other countries as well, particularly ones with majoritarian systems such as the U.K. and France (Piketty, 2018).

Majoritarian systems with a spatially even mixing of left-wing and right-wing voters can be problematic in that small differences in popularity of a party can lead to huge differences in representation. A party’s share of Congressional seats could decrease from 100% to 0% with a very small change in votes if voters were homogeneously spread across districts. However, the problem faced by modern majoritarian systems is due to differential concentration of left-wing and right-wing voters. Jonathan Rodden, in his book, Why Cities Lose: The Deep Roots of the Urban-Rural Political Divide shows this differential concentration based upon work with Jowei Chen. They look at each person’s nearest 250,000 neighbors. They choose 250,000 neighbors because the average upper chamber district in Pennsylvania contains around 250,000 voters. They find that over 25% of Democrats’ nearest neighbors are more than 70% Democrats whereas no Republicans’ nearest neighbors are more than 70% Republican and only 10% have more than 60% of their neighbors being Republican.

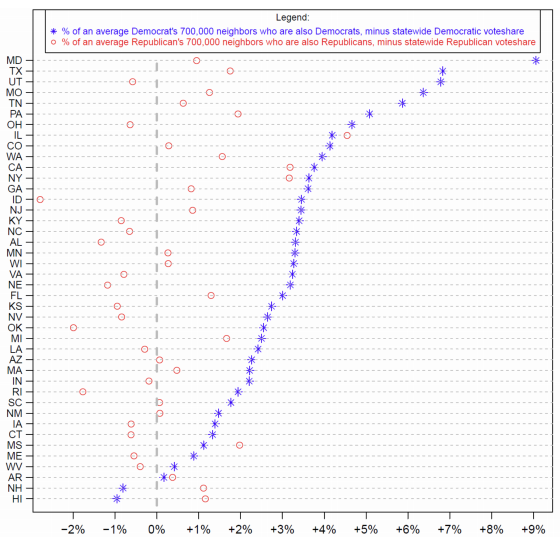

In a recent paper, Chen and Rodden (2018) do the same analysis and present the average share of Democrats in the nearest 700,000 neighbors of each Democrat and the average share of Republicans in the nearest 700,000 neighbors of each Republican. They do this by state. The results are presented below. Republicans are more concentrated only in five states: Arkansas, Hawaii, Illinois, Mississippi, and New Hampshire. Moreover, in most states, Democrats are far more concentrated than Republicans.

Table 2: The Geographic Concentration of Democratic and Republican Voters

Why does the greater concentration of Democrats lead to a failure of representation? The best way to understand this is to use Nicholas Stephanopolous’ concept of the efficiency gap. Stephanopolous (2015) computes wasted votes (all votes in a district for any loser in the district and the number of votes above plurality for the winner in a district). The problem is that the greater concentration of Democrats in cities than Republicans in rural areas leads to more wasted votes by Democrats than by Republicans. Since Republicans waste fewer votes, they are able to win more districts. In other words, they get systematically greater representation given their vote shares. Idiosyncratic differences across parties in representation average out. However, the differences we see these days in the United States, the U.K. and France as well as in other majoritarian systems such as Australia’s House of Representatives display systemic over-representation of rural over urban voters.

Overall, proportional representation does a better job at representing the will of voters in that political preferences of voters more closely match seat shares in a proportional representation system.

Duverger’s Law

One additional consequence of having a majoritarian political system is that there tends to be fewer political parties. In any given district and sometimes overall at the national level, only two political parties emerge. In this sense, the United States, with its two main political parties is a textbook example of a majoritarian system. Why does the electoral system help determine the number of political parties?

In a majoritarian system, there is only one winner. With a plurality rule for deciding the winner, this gives parties which are ideologically closer to each other a reason to combine forces into one party. For example, suppose that there are two left wing parties each of which garners 30% of the vote and there is a right-wing party which garners 40% of the vote. In a majoritarian system, the right-wing party will win even though 60% of the people prefer a left-wing party. As a result, the two left-wing parties have strong incentives to combine and form one party or at least voters will have strong interests in coordinating on one of the two left-wing candidates. In a proportional representation system, by contrast, having two left wing parties may attract overall more left wing voters. Maybe some ideological voters would only vote for one of the two. In that case, having both will bolster turnout for the left and thus the left-wing seat share in parliament or Congress.

This empirical regularity about the number of parties in proportional representation as opposed to majoritarian systems as well as the logic behind it was first pointed out in Maurice Duverger’s book Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State (Duverger, 1954). Modern day Australia provides a natural experiment which illustrates Duverger’s law. Australia’s Senate is elected using state-level proportional representation whereas Australia’s House of Representatives is elected in majoritarian districts. Whereas ten different political parties are represented in the Senate, the House is dominated by the Australian Labor Party and the Liberal-National Coalition (Rodden, 2019).

Rank-Choice Voting

One increasingly popular alternative to proportional representation in multi-member districts is ranked-choice voting in single-member districts. In a rank-choice voting system, instead of voting for one person or one party, voters rank alternative candidates. Then, top-ranked votes are tabulated for each candidate after which the worst overall performer is eliminated. If no candidate has reached a majority of votes cast, the votes for the eliminated candidate are reallocated to the next preferred candidates listed by the eliminated candidates’ voters. This system has been implemented in Alaska, Maine and New York City among other places. Moreover, somewhat similar systems which eliminate candidates in two rounds exist in states such as California, Georgia and Louisiana. Though there is very limited theoretical work or empirical evidence on rank-choice voting, switching to rank-choice voting would likely tend to moderate candidates and thus improve representation relative to a single-member district system with plurality voting. This moderation would probably be large given the current electoral system in the United States with highly partisan districts and candidates selected in highly partisan primaries.

Let’s look at an example. Suppose there are 3 candidates: one far-right candidate with support from 40% of voters, one moderate-right candidate with support from 35% of voters, and one left wing candidate with support from 25% of voters. Moreover, lets assume that right wing supporters prefer the other right-wing candidate to the left-wing candidate and that supporters of the left-wing candidate prefer the moderate-right to the far-right candidate. In that case, in a majoritarian system with a primary, the far-right candidate would defeat the moderate-right candidate in a primary and then the left candidate in a general election. However, with rank-choice voting, the left-wing candidate would lose in the first round of counting. After that, the votes of the left voters would be transferred to the moderate-right candidate, who would then defeat the far-right candidate 60% to 40% in the second round of counting.

Though rank-choice voting sometimes would lead to a more moderate choice when that choice would be preferred in aggregate by voters, sometimes it would not. Let’s now reverse the support for the moderate-right and the left voters from our previous example. We thus get: 40% support for the far-right, 25% for the moderate-right and 35% for the left. Let’s assume that the secondary preferences of voters remain the same (right-wing voters prefer the other right-wing voter to the left-wing candidate and left-wing voters prefer the moderate-right candidate to the far-right candidate). In this case, in the first round, the moderate-right will be eliminated and in the second round, the moderate-right votes will be transferred to the far-right. Thus, even though a 60% majority of voters prefer the moderate-right to far-right, the far-right candidate will still win even with rank-choice voting.

In addition, since the rank-choice voting variant of single member districts is still a single member district system, it will not fundamentally eliminate the problems associated with over-representation of rural interests due to greater spatial concentration of urban voters; it also won’t solve the problem of parties strategically drawing district boundaries to increase the seat shares of their parties.

Economic Policy

We now discuss how the number of parties can affect voter turnout and the types of political coalitions that form. Proportional Representation systems having a greater number of parties likely increases voter turnout. Some voters are only motivated to turn out to vote if they are ideologically similar enough to a party. Citizens who do not vote are much likely to be lower income and are more likely to support greater economic redistribution. Funk and Gathmann (2013) demonstrate that when Swiss Cantons converted from majoritarian to proportional representation electoral systems, voter turnout increased, representation of left-wing parties rose, and social expenditures increased.

Redistributive economic policy may additionally be de-emphasized in a majoritarian system. A majoritarian system shapes coalition formation. As mentioned earlier, in the United States, the cities support the Democratic party, the rural areas support the Republican party and the suburban areas swing between the two. The Democratic party could seek alliances with suburban voters on social issues or rural voters on economic issues. Since the suburbs are more electorally competitive, the Democratic party has shifted towards more conservative economic policy and more liberal social policy. Since the Democratic party needs a plurality of votes, it largely abandons rural voters and the issues they care about. However, under a proportional voting rule, the Democratic party would instead orient its policy towards policies that would get the greatest support rather than towards voters in swing districts. Thomas Piketty (2018) shows that, over the past half a century, left-wing parties in France, the U.K. and the U.S. have shifted towards away from redistributive economic policy as more educated voters have increasingly voted for the left.

U.S. Legislation

In this policy brief, we have demonstrated that majoritarian systems allow political parties to increase their representation by controlling the redistricting process. We have also discussed research which shows that majoritarian systems over-represent rural interests and under-represent support for economic redistribution. In this final section, we discuss policy changes that are feasible in the United States.

Is proportional representation feasible in the United States? Currently, ten states use some form of proportional representation: Arizona, Idaho, Maryland, New Jersey, New Hampshire, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington and West Virginia. In these states, some state representatives serve in multi-member districts which allow multiple parties to represent a district. Though these multi-member districts are small and thus don’t capture the main benefits of proportional representation, it would be easy to enlarge state districts or just get rid of them entirely. Voters then would vote for all representatives simultaneously as one unified state and a proportional representation rule could easily allocate seats based upon votes.

At the federal level, the United States Senate is not easily changed as representation in the Senate is constitutionally mandated. Given the difficulty of passing constitutional reform, moving to rank-choice voting would likely at least improve representation. It would not, however, be difficult to change the voting rules for the House of Representatives in the United States. In particular, the Constitution would not have to be amended. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there were multiple predominant systems of electing representatives. For example, it was common in the early 19th century for states to elect members to the House of Representatives using at-large voting. In this system, whichever party received a plurality of the vote at the state level would get all of that states’ representatives. This practice was banned with the Apportionment Act of 1842. However, it was weakly enforced and at-large elections persisted. In 1967, this changed when Congress passed and President Johnson signed 2 U.S.C. § 2c. Since 1967, majoritarian district elections for the House of Representatives have been required. It would only take an act of Congress to change the voting system from single majoritarian district elections to proportional representation.

Endnotes

[1] In some more complex proportional representation systems, voters cast ballots for both parties and candidates. I focus here on the simplest of proportional representation systems. Also, many countries such as Japan and Germany have mixed systems where citizens cast ballots both for particular representatives of a local district as well as for a party. The party votes determine how many additional at-large seats a given party will have in parliament.

References

Chen, Jowei and Jonathan Rodden, “The Loser’s Bonus: Political Geography and Minority Representation” (2018), working paper.

Coriale, Kenneth, Ethan Kaplan and Daniel Kolliner (2020), “Political Control Over Redistricting and the Partisan Balance in Congress”, working paper.

Duverger, Maurice (1954), Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State, John Wiley & Sons.

Funk, Patricia, and Christina Gathmann (2013), “How do electoral systems affect fiscal policy? Evidence from cantonal parliaments, 1890–2000.” Journal of the European Economic Association 11.5: 1178-1203.

Piketty, Thomas (2018), “Brahmin Left vs Merchant Right: Rising Inequality and the Changing Structure of Political Conflict.” WID. world Working Paper 7.

Rodden, Jonathan (2019), Why Cities Lose: The Deep Roots of the Urban-Rural Political Divide, Basic Books.

Stephanopoulos, Nicholas O., and Eric M. McGhee (2015), “Partisan gerrymandering and the efficiency gap.” U. Chi. L. Rev. 82: 831